Interview by John Mulrooney

As a poet, novelist, memoirist, translator, editor, and publisher, Joe Torra has been an integral part of the literary scene in Boston and beyond for over 25 years. I recently had the chance to sit down with him and talk poetry, music, painting and mushrooms.

Boog City: What’s the difference between God, Jesus, and the Holy Ghost?

Joe Torra: I don’t know. Have you read my memoir (Who Do You Think You Are? Reflections of a Writer’s Life, forthcoming from PFP publishing) already?

Honestly, it just arrived and I’ve just cracked it. But the first impression makes the question seem relevant.

Yeah, but I don’t know what the difference is. I never could figure it out. I think God is supposed to be the father. Jesus is the Son. I don’t know who the Holy Ghost is. I think [poet] Gerrit [Lansing], but, yeah, it’s a question that figures in the memoir.

When the memoir started out, I didn’t really know what it was going to be. But I started thinking, you know, maybe I’ll write a little bit about writing. And it really ended up being about everything. Not a lot about everything, but just little snippets here and there. And one of the things I write about, because I write a lot about Taoism, and my, you know, transformation into Chinese philosophy and Taoism, because I was raised a Roman Catholic kid, and I did try to be a little religious when I was young, and I could never sort it all out. It never made any sense to me. And I was very young when I realized that Catholicism meant nothing to me and had nothing to offer me.

But I write about that in the book, and eventually what ends up happening is writing, music, painting. And later teaching, drug addiction, alcohol, drugs. Once I was middle-aged it was mostly pot but a lot of heavy pot use and drinking. And also mental health stuff, because I’m diagnosed as bipolar. So all sorts of things ended up in there from my childhood to current stuff. It’s in no necessary order.

I don’t mention a lot of people because there are just too many people, and if I put so-and-so in I’d have to put someone else in. I did write a fair amount, here and there about Gerrit, and [poet and publisher] Bill [Corbett] who were teachers of mine and really important to me, so within the context of being lucky to have some older mentors as a writer growing up. And TJ, my friend, TJ Anderson, who I don’t see that much anymore, but we’re still really close. And even Bob D’Atillio [anarchist historian and character in my novel The Bystander’s Scrapbook (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2001] ends up making an appearance. And then there’s a lot about getting published and struggling and my attitudes about what to write and form and the academy and the poetry world. And so all sorts of stuff in there.

So, it’s not just a craft book, it also travels into lots of other areas of your life.

You know, the thing is probably less about writing than other things. And it’s not a craft book, although I talk about craft, but you know, it just didn’t end up being that. It’s not the kind of thing that your creative writing instructor would say, “This is useful for creative writing classes.”

It reminds me of something that Gerrit once said to both of us, I think actually speaking about the poet Amanda Cook, that, and I’m paraphrasing here, one of the highest achievements in art is when the life lived and the art made are almost indistinguishable.

Yeah, yeah, I feel that way. And certainly, Amanda, not only do I think she’s a really amazing, top notch, maybe that’s when we use the words great writer, but what I love about her is that it’s just life. It’s for her. It’s like making a good pot of soup. She doesn’t distinguish. And she’s not a careerist. I mean, I know even as a publisher, I’ve had to work real hard to say, “Hey, I’m publishing Let The Bucket Down[: A Magazine of Boston Area Writing], send me some work.” I have to pull teeth. And I remember her years ago, we’d have those Sunday morning meetings at the Grand Cafe [in Somerville, Mass.] around when I first met you, and she would come and you know, all the guys would be talking poetics and arguing. And she’d be sitting there knitting, like with this grin on her face. And I loved it. And I knew, like, while she just don’t care about any of this stuff, and she’s a better poet than most you’ll meet.[And I knew that she just doesn’t care about any of this stuff, and she’s a better poet than most you’ll meet.]

So many different kinds of work go into the work of writing. Your extensive output clearly illustrates this. I know you’re at work on a follow up to Time Being (Quale Press, 2012), which I hope to talk about, but that’s concurrent with your translation projects and you’ve always had editorial projects going on.

The translation is an amazing project. For me, it’s kind of replaced what editing was for me before. I talked about editing [Stephen] Jonas because editing was a big part of my writing life for so long. And you don’t have to do that stuff, the other projects, but some people do. It’s like, you might run a reading series, you might be an editor, you might start a press, and somehow editing got under my skin early on, with [editing and publishing] lift [magazine]. And even before that, I published a little couple of little zine things way back when when I was in college, and …

Do you still have any of those somewhere?

I do. I don’t know where they are. I started a little reading series at this cafe in Boston on Beacon Hill, it’s not even there anymore. It was this kind of a Middle Eastern cafe. The owner was Achmed, and we had a little reading series there and an open mic, the kind of stuff you do when you’re starting out. And I did a little zine and published some of the people that were reading down there. I’ve lost touch with most of them. So it just got under my skin.

And I think that becomes kind of part of your schooling. I started with Jonas in the late ’80s, and just finished co-editing the City Lights book a few years ago. There were years when I had all his papers scattered all over the basement here, and was just constantly living it. And so I’ve always had that. But so now that that’s done, and I’m not publishing anymore.

So falling into this translation project has been amazing. And I met Yonghong [Gu] at UMass Boston. She was a visiting scholar. And actually, she was here for business because she’s was a businesswoman in China as well. But she was auditing a class I taught—Six American Authors—and I realized that she knew yards about Chinese poetry and she would start reciting Tu Fu, Li Po, and others off the top of her head. So we ended up getting closer. She was writing a little poetry which we discussed and one day she said to me, “You know, I’ve started a novel. It’s in Chinese.” And because I don’t speak Chinese, she would very roughly translate some things. And I was like, ‘Yeah, that sounds like it, you’ve got something going on there.”

And so I said, You know, I could help you translate this into English. And that’s how it started. And now, two-and-a-half years later, we’ve got over 400 pages of English. She writes the Chinese and we translate together, and, as her English has gotten better, it’s gotten easier. So it’s been this really great thing. It’s funny, because she always says to me, “You’re my teacher,” but since I’ve lost Gerrit and Bill, in some way, she’s become my teacher. And because my connection and love for the Chinese has been so strong over the years, I mean, every day I’m reading Chinese philosophy, or poetry or something, she turned me on to a bunch of Chinese fiction writers I never knew. And it’s a sweeping book that goes across China; the story of one family over many years. There’s amazing vast goings-on across the whole country, and the scenery and trucks and trains, and the mountains and the big rivers. Yonghong is really a beautiful writer.

One of your earlier books of poetry After the Chinese (Pressed Wafer, 2006) reflects this lifelong interest in Chinese literature and Chinese thought. How did that come about?

Certainly, over half a lifetime ago. I think I first came to the Chinese through the Beats. And Rexroth for sure. But I came to Buddhism first through Kerouac and Ginsberg and Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder, and their Buddhism led me to China and Japan, but it was China that seemed to really take hold for me. And then eventually to Taoism, the philosophy of Taoism, which is incredibly endless. It’s this kind of endless thing you can keep investigating. So that came up decades ago, and when I wrote After the Chinese, I think I’ve been reading the Chinese poems for so long that they sort of took root. They’re not really translations at all. However I think my most Chinese book is the first Time Being book. I’m writing a second one now.

Can you expand on that?

Sure, for a few reasons. Because of the Taoism, the formlessness of the text. Taoism is all about formlessness. And this sense of emerging and returning from nothing to something to nothing, the way the narrative in Time Being does, it kind of swells up and goes away. Sometimes you’re not even sure where one event leaves and another one arrives, and also the Chinese concept of time, which is very important. One thing I’ve learned a lot from translating with Yonghong, is the Chinese philosophy of time. Their philosophy is so different from ours. For example in the West, you must take steps. Let’s say, you’ve got to get to the top of the mountain, you take steps 1-2-3-4-5. In China, we just put you on top of the mountain, you don’t take any steps to get there.

That’s really interesting. Time Being is one of your books that stays with me the most and one of the things that’s so compelling about it is this sort of fluidity, not just with its own narrative but the material of it. The long passages work to define or redefine what a lyric is, and while it has such richness it also brings up a question about the nature of form that’s as practical as it is philosophical. When you are writing Time Being, what are you? A novelist? Are you a poet? And how does this work for presenting work in the world these days?

Well, it was really strange because Time Being is just sitting in limbo. I don’t think anybody, or hardly anyone who has read it, gets it. One of my colleagues taught it in his grad class just this week. I went and spoke and that came up constantly. Well, it’s a hybrid I suppose … He’s a fiction writer and kept saying, “Well, I read it as a novel.” I was like, it’s absolutely not a novel.

You know, I see it as a long poem, but it’s almost formless. And I think I’ve always pushed forms around. I go back to my first book of poems, Keep Watching the Sky (Zoland Books, 1996). And they’re just prose poems in there. There’s all this collage stuff. You know, I look at The Bystander’s Scrapbook, which is a collage, you know, a Paul Metcalf kind of a book and Tony Luongo (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000), which is an non-punctuated novel, but 218 pages.

So I think it’s not deliberate. But I tend to really push forms around. And I’m not that worried about conforming. I don’t really worry about that stuff, but it can be as if I’m spiting myself, because I’m thinking, “Nobody’s gonna publish this, and nobody’s gonna think about it. And how do you even send something like this out to a magazine?” They’re like, “What is this?” Editors ask me to send some poems and when I do that, they always write back and go, “could you send me a couple of regular poems?” But music, I think Time Being is a poem because it’s music and anything I’ve done, the conventional poems, even editing, Tony Luongo is music. I mean, you can’t write a non-punctuated novel without having a sense of music and syntax.

I was going to ask about music next.

Time Being to me, especially the first book, and even this one I’m working on, is like, I imagine Cecil Taylor doing one of those weird steps up to the piano and then, just an hour-and-a-half later, an improvisation has emerged.

So how does your playing music fit into your sensibilities as a writer?

I don’t think it fits in much at all, at least in a way that I understand. I’m sure it feeds it. But you know, I’m … I’m not a musician. I mean, I can play three chord punk rock [as part f the band band The First Supper]. And barely. I think what I’m more proud of is the songs. I think I can write some catchy pop songs, and because I’ve been listening to pop music since I was so young. And I’m proud of some of the songs I’ve written. But I can’t read music. I don’t understand theory … nothing. So it’s just primal. It’s like painting. The painting fits in more.

How does that work?

I think these paintings I’m making are like Time Being, you know? The process fits in more. But I think like a three-chord punk song, it just feeds my soul. Because I love it. And I feel like if I can do a three-chord punk song, why shouldn’t I? But I know the difference between me and [Boston musicians like] Anthony Kaczynski or Dave Yanolis. But I’ve never tried to sell my paintings or show them. I should give some away but I don’t even want to give them away. I love them.

Like children?

Yes. I think so … Painting is closer to my writing. My paintings are working through Taoist feelings and thoughts all the time. And so I feel like when I’m writing Time Being or I’m making one of these paintings, I’m really engaging deeply in this kind of spiritual exchange. I do feel great connection when I’m playing music live, especially. And I do feel connected spiritually and everything, but it’s, it’s just different. It’s just not the same.

We talked a little before about your editing practice. The journals Let The Bucket Down and earlier lift. How many issues did lift have?

Sixteen in four years, I think.

Are they all archived somewhere?

No. I think I have one complete set left. I’ve tried to contact libraries and tried to sell a copy. I’m never even asking a lot of money. Nobody’s interested. But I’m proud of the fact that when I started lift, I started publishing a lot of younger writers who couldn’t find a place to publish. And we were publishing at a time, 1990, things were different. Now a lot of walls are broken down.

I find the more younger writers can do experimental stuff, they can write a song or work in other media, but back then, when I was younger, you had to make a choice. You know, are you part of the New Criticism or are you part of the New American Poetry line. And I was clearly the latter and I clearly wanted to make a magazine in this city that supported that. And I wanted to be supportive of young writers; a lot of the ones I was meeting at [the] Word of Mouth [reading series hosted by poet Michael Franco], and then nationally, because as soon as I started doing it, I was connecting with Kevin Killian out in San Francisco. And he was connecting me with people, Bill was connecting me with people.

And so I understood my history, because one of the first people I looked up and got work from was Cid Corman who did Origin Magazine and he was living in Japan, and he sent me work, and we had a great correspondence for a while. I wanted to make a Boston zine, in the tradition of Origin and [John] Wieners’ Measure and Gerrit’s Set and Fire Exit with Fanny [Howe] and The Boston Eagle, you know those things Bill was doing back in the ’70s.

Well, we just reprinted one of those for the Lewis Warsh issue.

Oh, great! That’s wonderful. Let’s see, Lewis and I met, it must have been through Bill. I met Lewis and many people at Bill’s dinner table. Bill could be ornery. He liked me. And I loved him, despite our differences and problems we’d have. But his fuckin’ kitchen table was part of my schooling.

I remember the first time I was there, which was when I met you first I believe, you pointed at the dinner table and said, “That’s your M.F.A. program.” Do you have a sense that this editing and publishing work is related to community, or how does it fit in?

There was a time when I was young before we met, I was everywhere. And that’s important. Once you really start writing there’s also a point where you think about that differently. When I wrote my first novel, and was really writing my first poems, I was searching. When you’re trying to figure out who you are, you’re everywhere, all the time. And as time goes on, well, at least for me, I became a little disillusioned. I also worked with Bill on Pressed Wafer, and I believe in community more than anything, and it’s one of the reasons I did it. I didn’t do it deliberately.

But now I feel it’s a new world, a new poetry world out there. I mean, like, I love what Christina [Davis, director of the Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard] is doing. And she’s amazing, but I don’t go to everything now. And then once you have kids that changes things too. But as time has gone on, yeah, I’m much less out there. Because I’ll tell you, right now, if I’m going to go out, I’d rather go see a band. But I guess what maybe I’m also considering is that community manifests in a number of different ways, right, like showing up at the readings is not the only way it does. And the editing and the publishing were definitely part of that.

Well, one of the other things that has expanded in your life is your teaching.

Right, which has a way of fostering a community in a sense. Well, some aspects of it are broader, but some aspects of it can’t be quite narrow, when you work closely with a student. And that’s a sphere where community continues to be present even as the manifestation of it shifts. I’ve given half my life to Stephen Jonas, and now I give it to students and, believe it or not, I connect with students and always seek to connect them with the wider world.

I have a student who’s quite brilliant, whose graduate thesis on Olson I’m reading. It’s great work. I hooked him up with Kevin Gallagher [of sPoke] and he wrote a review of the Jonas book, because I know this kid needs to start publishing if he’s going to apply for Ph.D. programs. But my sense of the community has changed as it has. It’s bigger. It’s, when you think about the difference between the original Boston [Poetry] Marathon, and there was a real purpose and aesthetic there that Sean Cole and Aaron Kiely and then you and Jim [Behrle] were doing, it was like a feast. Now it’s more like a buffet. It doesn’t mean I don’t love it. It doesn’t mean I don’t love my friends who write. I do.

Like a feast. You mentioned soup before. Cooking is an important part of your life. I wonder how it relates to writing. Or your mushroom foraging?

Yeah, no cooking. Food is definitely a big part of my life. In fact, that’s in the memoir, hanging out in the kitchen with my mother. It goes way back. And mushrooms go way back too; they have always been important to me. I still pick them. I still forage. I love to get out to the woods. I find it plunging me right into the world of the Tao. And mushrooms are these strange things that might not even have originated on earth. And I love to eat them. And I love to walk in the woods.

When I grew up my dad, well, we didn’t have a good relationship, but he was a hunter and I grew up tagging along with him and his buddies in the woods and learning a lot about the outdoors and deer and small game and fishing. And that’s where mushrooms fit in. Because I can stay in touch with that and I don’t have to have a gun and kill something. I don’t want to kill anything. I don’t even want to kill a fish.

Does that come back around to our earlier conversation about the intersection of art made and life lived?

Yeah, it’s the life. And I learned that from people, from poets and musicians. Because originally … and maybe we all do this, we fall in love with the idea of being artists or musicians, and we think it’s this thing, like a goal. And it took me a long time to realize, no, it’s already part of who I am, and it’s part of my life. And my children are as important as getting published. And eating a good meal is as important and maybe cooking a good meal is as important to my well being as writing a poem.

I used to read a lot of Alan Watts when I was a kid. And he used to say things like, “Look, if you realize you got to mop your floor, and you can enjoy that, you should go do it. But if, you’d rather be out walking somewhere or doing something else, then you don’t do it.” And that’s another thing about Time Being, the domestic. I think I’ve learned that from women poets, like Bernadette [Mayer] and Fanny. Also Amanda, she has taught me too. But also the Chinese poets like Mei Yaochen, who was a poet of the domestic.

Look, you’ve got to to change diapers, you got to cook, you’ve got to wash your dishes and do your laundry. Why separate that? That should be material for your work. And that’s why one minute you’re up in the Tao and in the heavens. And then the next minute, your transferring clothes from the washer to the dryer. It’s all the writing. It’s the life.

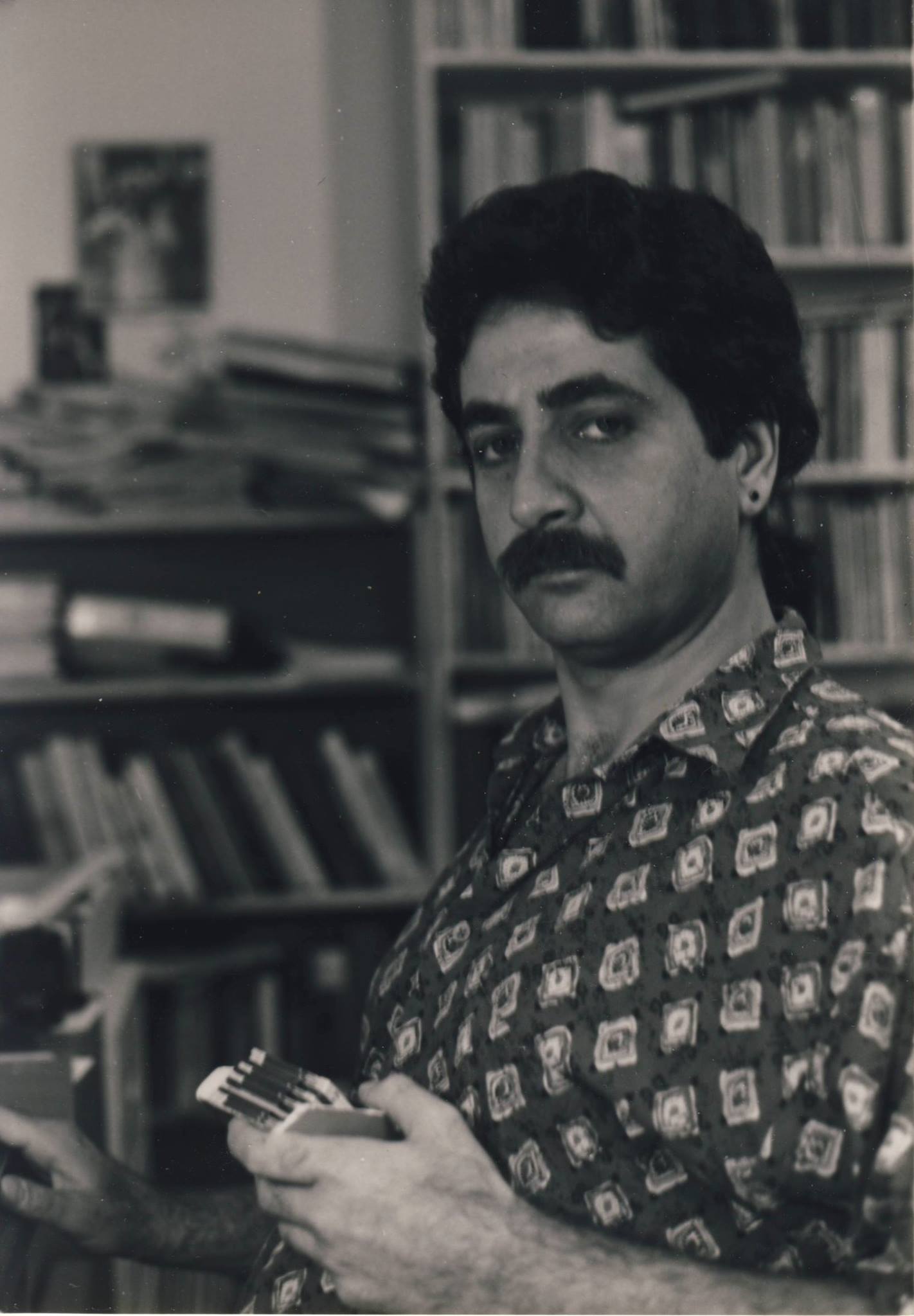

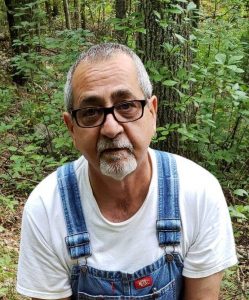

JOSEPH TORRA (http://joetorra.com/mygroundtrilogy.html) is a Boston native. Poet, novelist, editor, and memoirist, his books include What It Takes, What’s So Funny, They Say, My Ground Trilogy (fiction); Keep Watching the Sky, After the Chinese, Time Being, Duck Tour: The Movie (poetry); Call Me Waiter, and Who Do You Think You Are?: Reflections of a Writer’s Life (Forthcoming memoir). Currently he is co-translating a novel from the Chinese author Yonghong Gu. He is a painter and plays in the rock and roll band The First Supper.

JOSEPH TORRA (http://joetorra.com/mygroundtrilogy.html) is a Boston native. Poet, novelist, editor, and memoirist, his books include What It Takes, What’s So Funny, They Say, My Ground Trilogy (fiction); Keep Watching the Sky, After the Chinese, Time Being, Duck Tour: The Movie (poetry); Call Me Waiter, and Who Do You Think You Are?: Reflections of a Writer’s Life (Forthcoming memoir). Currently he is co-translating a novel from the Chinese author Yonghong Gu. He is a painter and plays in the rock and roll band The First Supper.

JOHN MULROONEY (https://solsticelitmag.org/author/john-mulrooney/) is a poet, filmmaker, and musician living in Cambridge, Mass. He is author of If You See Something, Say Something (Anchorite Press) and co-producer of the documentary The Peacemaker, from Central Square Films. He serves as poetry editor for Boog City. He records and performs regularly with a number of musical groups in the greater Boston area and is an associate professor in the English department at Bridgewater State University. His work has appeared in Fulcrum, Pressed Wafer fold’em zine, Solstice, The Battersea Review, Poetry Northeast, spoKe, Let the Bucket Down, and others.

JOHN MULROONEY (https://solsticelitmag.org/author/john-mulrooney/) is a poet, filmmaker, and musician living in Cambridge, Mass. He is author of If You See Something, Say Something (Anchorite Press) and co-producer of the documentary The Peacemaker, from Central Square Films. He serves as poetry editor for Boog City. He records and performs regularly with a number of musical groups in the greater Boston area and is an associate professor in the English department at Bridgewater State University. His work has appeared in Fulcrum, Pressed Wafer fold’em zine, Solstice, The Battersea Review, Poetry Northeast, spoKe, Let the Bucket Down, and others.