by Susmit Panda

The Hierarchy of the Pavilions

Ben Mazer

MadHat Press

“All these ignoble qualities in literature arise from one cause—from that passion for novel ideas which is the dominant craze among writers of today.”

Thus begins Longinus’ paragraph on what he refers to as “literary impropriety.” Against the hyper-manic, hackle-raised métier of modern culture, a practitioner of the lowly Written Word must take heed. Poetry in the 21st century, while full of fireworks of “the new,” is also full of inhospitable mist.

This is not to mean that progress is essentially inimical to art. But in the case of poetry, progress is subtle and gradual. Poetry can neither breathe nor grow, except along the path of tradition. It is not for nothing that American critic Harold Bloom traced the achievements of such modernists as Joyce and Beckett back to Homer. Innovation can neither be a dictate nor a decision, except in boardroom meetings. Amid the flutter and clutter of the decidedly “new,” Ben Mazer’s The Hierarchy of the Pavilions arrives.

Mazer’s poetry has always resisted the (postmodern) temptation (and idea) of the new. His latest collection is no exception. The poems here are vivid without being banal; intense, without going haywire, purposely or not; and lushly reminiscent of the profoundest throbs of life, which, when felt anew along the beatings of the heart, soars beyond the poetic register, and reestablishes the perpetual nod of being and having been. It is not amiss, therefore, that his immediate muse is “memory” (which he referred to as man’s “guiding star” in one of our email chats) — a subject he keeps returning to, much like the eponymous heroine in Madame Bovary does to the memories of the masked ball. Memory is Mazer’s “occupation.” Indeed, his entire poetic oeuvre is a concentrated wooing of memory.

The Hierarchy of the Pavilions is far from an ambitious undertaking, but instead it is the continuation of a journey, which, while it may switch lanes, cannot abandon the course. It is a page-turner (how often does that happen for a book of poems!) and succeeds in convincing even the disinterested reader of its appeal. Take a look at the following fragment from the first sonnet of “Eight Sonnets: The Beginning of Something”:

“…I’ve got a lot to say

in terse enjambment of the life that wrought

from the encampments of real history

the man who stands before you in his mystery

and the excessive drama of his thought…”

The rhymes are predictable and the sentiment itself spotlights the core of poetic inspiration. But what distinguishes it, makes it Mazerian, as it were, is the “pavilionic” awareness. The word pavilion comes from the Latin papilionem, which denotes a tent in the shape of a butterfly’s wings (papilio meaning butterfly). For Mazer, the tent or pavilion is the ultimate abode of self, which is simultaneously anonymous and historical. Mazer’s hierarchy is his own design—a fact of being which captures the unrecorded dilemma of the 21st century poet. The poet concludes the sonnet with a near-majestic usher of individuation, which is deceptively anonymous:

“how knowledge was from outer action got

internally, as holy men might pray,

and how the tiger captured what he sought.”

For Mazer, individuation seems to be a conscious enterprise, which, like all such projects, is at times enlightening, other times, depressing. He is constructing his own image through his poems and beyond, and he has a well-placed strategy for the same. In that regard, one of the most enriching readings in the book is the collection of apothegms, dryly titled “The Foundations of Poetry Mathematics.” An assortment of sixty-odd maxims, it is witty and wise by turns, and immensely stimulating. The following maxim, for instance, reminded me of Wallace Stevens:

“The moon is green cheese. This has long been established as fact.”

And yet Mazer’s forte is the lyrics. His lyricism, especially when it comes with a dose of poetic intelligence, is delightful. In the second sonnet of the series, the closing lines somehow[?] reminded me of the closures of Ghalib:

“how with his manners, eventually he bought

the dream itself and paid it dividends

out where poetic fury never ends.”

The almost-title poem, “The Hierarchy of the Pavilion” (the jacket, apropos, shows an outline of New York-esque high-rises stripped of their miasmatic dazzle and reduced to imaginative ordinariness), perhaps best captures Mazer’s breathlessness, or “poetic fury.” The poem is apparently a “fragment” and is composed in three parts. It is delightfully verbose, maddeningly dense, and almost impossible to crack. The words Mazer uses are odd and orgasmic. The lexical innovation, the bend and the boom, the sudden lift, the dying fall—all exhibit the sheer pleasure of slurping the soma juice of words. And the reader is tempted to partake of the spills.

Mazer is not afraid of using archaic words; in fact, the archaic throbs like a pulse throughout his creation, almost in a Spenserian fashion (Spenser is one of Mazer’s favorite poets). Such word-drunkenness is near-extinct, which is a pity. The priest is allowed the rapture, at times, of discovering his Lord as a clutter of gods. Verbosity is often dismissed as a juvenile sport, which may not always be true. And so, in Mazer’s case, the title poem is the one that best mirrors the poet’s persona. A shade of such drunkenness is perceptible in Mazer’s Solomonic love poems. Here’s a 15-line sonnet, for instance:

“O how I long to hold your lumpy breasts,

as smooth as peaches, strawberry-tipped, and cool,

relaxing and warming to my thawing hands

beneath your sweater, moonlight, starlight drool-

ing through the window where you asked to spoon,

peering over your shoulder, warm my chin,

‘to nestle in your hair, to kiss your neck,

feign sleep in favour of amazement’s wrack

to let you sleep, and wonder at the dreams

that fill your soul, while moonlight stitches beams

of progress and desire across the hours,

and archetypal elementary schools

are symbols of the circular desire

that flickers in your eyes and in your breath,

from birth to cemetery, love to death.”

Such directness of expression with which the poem begins is rare these days and is thoroughly delightful and equally relieving to come across. This is the language of poetry, the sheer transparency of emotion. Phrases like “amazement’s wrack,” “starlight drool-/ing through the window,” and “moonlight stitches beams” are conspicuously romantic. Note that the entire poem is a single line, which is yet another rarity in modern American poetry. The underlying sentiment is universal. Mazer is not keen on developing new idioms, though, which might be a foible. There is a freshness in the lines, which, while neither stylistic nor artistic, does not fail to convince the reader of its penny plain power.

At the same time, it may be noted that Mazer seldom ventures into different forms of poetry. More often, he is content with a single style, a stock form of composing in couplets and occasional quatrains, all written, more or less, in iambic pentameter, although he does switch to free verse from time to time. For a poet who counts on his “subconscious” as devotedly as Mazer, such monotony, if I may use the term in a purely literal sense, is unsurprising. Although he referred to himself as a “technical wizard” in one of our chats, Mazer scarcely resorts to newer tricks. Nonetheless, is not Alastor a higher poet than Shelley, precisely because the former has nothing whatever to do with a pen and a piece of paper? Mazer is, therefore, a poet and a metaphor of one.

Mazer’s poetry is characterized by the intricacy of felt truth. In “The Foundations of Poetry Mathematics,” Mazer writes that “the mature poet aspires to greater incomprehensibility and less complication.” The same is true for Mazer himself. Consider, for instance, the lyric “Poetry had stopped.” The poem begins with concise matter-of-fact observations and builds up to the following inimitable lines:

“People who don’t exist meet, fall in love;

these parallels marked by an earlier time

have random places in time’s slow and sifting

annunciation of our proper tone.”

This is clearly decoding and representing the truth as it is. The lines are ungovernably intricate; “proper tone” is abstract, or, let’s say, “incomprehensible;” “slow and sifting/annunciation” is smart in its juxtaposition of the lexical positive and the factual negative; the general feel of the section seems to be somewhat pessimistic in its gradual realization. If I am not mistaken, the closing couplet—“Morning ascends. This caw caw almost spring/ was early in our own day a beginning.”—is a tender, and deceptively indifferent, lament on the cessation of (poetic or artistic) history. I am not sure what to make of “storm-starred mother,” although it does hint at some past sublimity (or idea thereof) which has passed the speaker by. The inference seems the more plausible since the “storm-starred” mother is said to be “hackling” “to the throne.”

Imagine Lady Macbeth angering after the ever-concretizing dagger, which continues to dangle at best before the gore-thirsty aspirant! And yet, suffused with biblical terms, which only accentuate the symbolic intention of the piece, the poem may be read as a quasi-nostalgic response to the fall of grandeur. Indeed, the way it starts—“Poetry had stopped”—is majestically abrupt, beckoning us to the spectacle of some tragic cessation. It is as if Mazer were responding (rather idly?) to the fury of a mournful Auden in the latter’s “Funeral Blues.” Mazer is apparently pondering the stopped clocks.

Come to think about it, Mazer is as much Audenesque in word as he is Shelleyan in spirit. Consider the following opening lines of an untitled poem:

“The rainy blur of poetry,

an inky wash the stars have hurled,

impatient to erase the world,

climbs up the bus steps after me.”

The conversational tone does not come at the cost of poetry. The rhymes seem miraculously accidental, like unwitting mirror images happening across each other at sudden bends in the street. Somewhere in the middle, enter the following couplets, which are sublime:

“The night has fallen on its head,

where fairy children are in bed,

but in the thickness of the fog

mankind pursues a homeless dog.”

The last line of the above fragment is a mark of poetic genius which, instead of unsettling, only confirms itself. This is poetry which does not belong to a particular time, age, or style. It exudes an uncontroversial permanence. The lines are immediately memorable, almost canonical, and imagistically perfect. Language, for Mazer, is not prostituted to a medium.

While Mazer’s lyricism might not live up to the highly contrived standards of current poetry, his poetry deserves a place in the canon of classic American poetry. His latest collection, rounded off with a sparkling afterword by Philip Nikolayev, is further evidence of the same. His poetic intensity, lyrical magnetism, and bewitching sense of persona continue to mesmerize your senses. The book is enriching and debauching at the same time, packed with power, and earnest in the lilt and tilt of its journey.

SUSMIT PANDA, born in 1996, is a poet living in Kolkata, India. His poems have appeared in Coldnoon, Indian Cultural Forum, Guftugu, The Boston Compass, and The Journal (London), and are forthcoming in Fulcrum: An Anthology of Poetry and Aesthetics and in 14 International Younger Poets (Art and Letters).

SUSMIT PANDA, born in 1996, is a poet living in Kolkata, India. His poems have appeared in Coldnoon, Indian Cultural Forum, Guftugu, The Boston Compass, and The Journal (London), and are forthcoming in Fulcrum: An Anthology of Poetry and Aesthetics and in 14 International Younger Poets (Art and Letters).

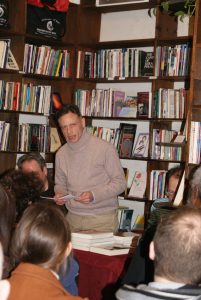

BEN MAZER was born in New York City in 1964, and was raised in Cambridge, Mass. As an undergraduate, he studied poetry with Seamus Heaney at Harvard University. Afterward he completed an M.A. and Ph.D. in literary editing and textual scholarship under Christopher Ricks and Archie Burnett at the Editorial Institute, Boston University. He is the author of 10 collections of poems, including Selected Poems and The Glass Piano (both MadHat Press), and Poems (Pen and Anvil Press). He is the editor of Selected Poems of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman (Harvard University Press), The Collected Poems of John Crowe Ransom (Un-Gyve Press), Selected Poems by Harry Crosby (MadHat Press), and Landis Everson’s Everything Preserved: Poems 1955-2005 (Graywolf Press), which won the first Emily Dickinson Award from the Poetry Foundation. This year Spuyten Duyvil will publish Ben Mazer and the New Romanticism, a book-length critical study of Mazer’s poetry by Thomas Graves. Mazer is currently editing The Collected Poems of Delmore Schwartz for Farrar, Straus & Giroux (2022). He lives in Cambridge, Mass. Elizabeth Doran photo.

BEN MAZER was born in New York City in 1964, and was raised in Cambridge, Mass. As an undergraduate, he studied poetry with Seamus Heaney at Harvard University. Afterward he completed an M.A. and Ph.D. in literary editing and textual scholarship under Christopher Ricks and Archie Burnett at the Editorial Institute, Boston University. He is the author of 10 collections of poems, including Selected Poems and The Glass Piano (both MadHat Press), and Poems (Pen and Anvil Press). He is the editor of Selected Poems of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman (Harvard University Press), The Collected Poems of John Crowe Ransom (Un-Gyve Press), Selected Poems by Harry Crosby (MadHat Press), and Landis Everson’s Everything Preserved: Poems 1955-2005 (Graywolf Press), which won the first Emily Dickinson Award from the Poetry Foundation. This year Spuyten Duyvil will publish Ben Mazer and the New Romanticism, a book-length critical study of Mazer’s poetry by Thomas Graves. Mazer is currently editing The Collected Poems of Delmore Schwartz for Farrar, Straus & Giroux (2022). He lives in Cambridge, Mass. Elizabeth Doran photo.