by Kurt Hemmer

Collected Plays

Gregory Corso

Tough Poet’s Press

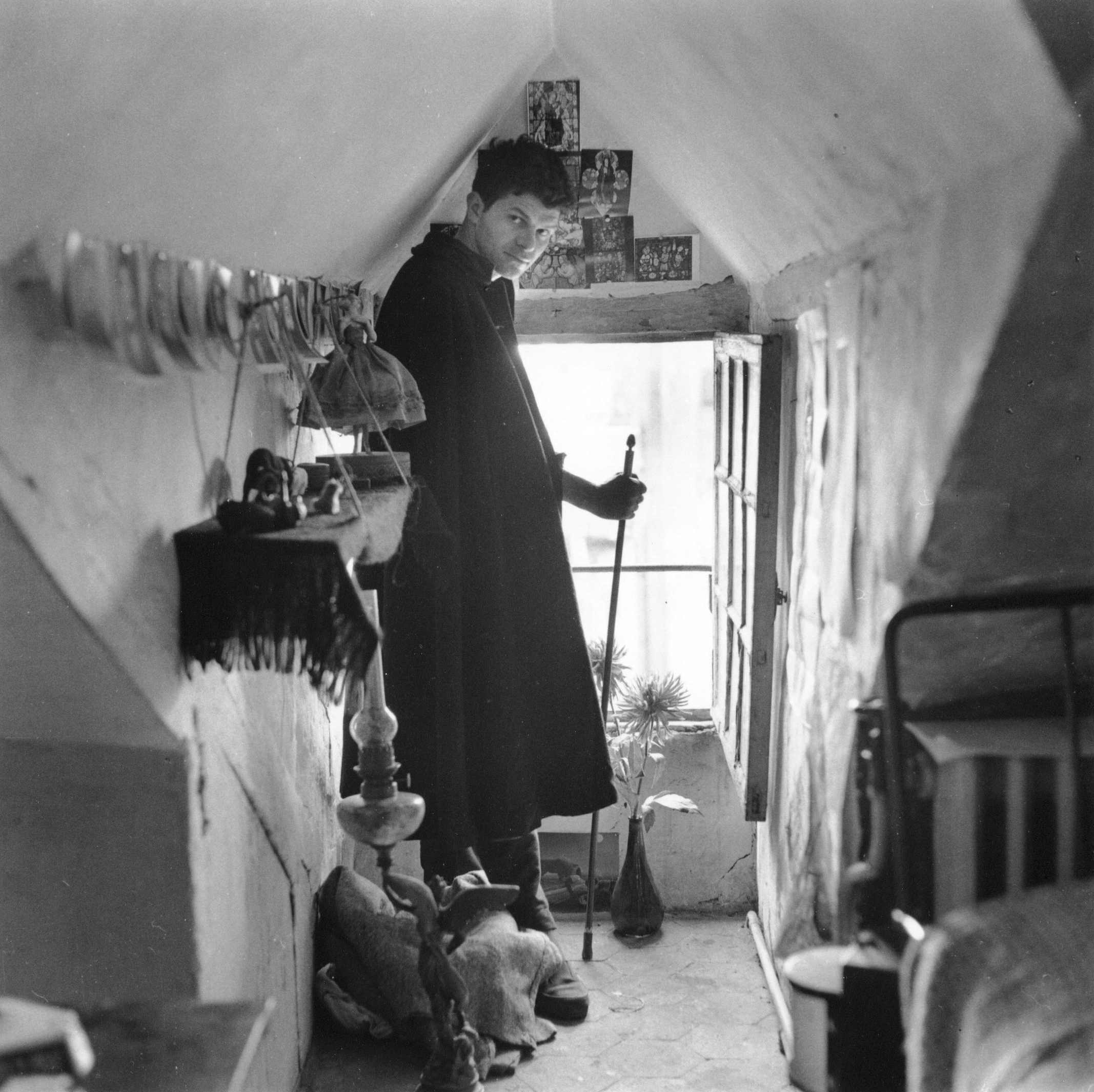

It must feel like a thankless job trying to keep the flame of Gregory Corso in the public eye. In the better part of the second half of his life, Corso did his damndest to destroy his literary clout. But Rick Schober is fighting the good fight for the writer that even Allen Ginsberg thought, at times, was the best poet of The Beat Generation.

Collected Plays is just what it says. It is not the complete plays. Schober even admits that it is nigh impossible to determine which of Corso’s plays was even his first. The Death of a Beautiful Boy might be his first play, but Schober does not include it here because Corso did not wish for it to be published. A play called A Prehistoric Day (1953) “a short comedy about an attempted drug deal involving a sloth, a sabre-toothed tiger, a mammoth, and a giant lizard,” which begs to be compared to a Michael McClure play, was too undecipherable to be included.

Way Out, A Poem in Discord, which was written in 1956, published and performed in 1974, called “more play than poem” by Ira Cohen, and almost published in Gasoline (1958), was not included because it also “lacks the humorous spirit of his other plays.” The Beats were not known as playwrights. Michael McClure and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) were the only Beats praised for their drama. What we learn from this collection, or what is reinforced, is that Corso, one of the youngest Beats, had a top-rate imagination that was grinding away before many of the other Beats had even gotten started.

The collection starts with Untitled Play (1952), which reads like a type of Theatre of the Absurd. It was found “unpublished, abandoned” at the University of Texas at Austin, and might be Corso’s first play. It is a parody of upper-class English manners. A guest, Mr. Blots, arrives at Hedy’s house declaring that he has tied his son to a willow tree naked and left him there to rot. A bug is discovered on the rug, but Blots refuses to kill the “harmless creature.” The Mother of the house squashes the bug when it crawls up her leg and she faints. The guest Mr. Mudd disposes of another bug in the fireplace to a burst of applause. A roach is discovered and Blots pulls a sword off the wall to protect it. The roach is crushed by the servant, Paul.

As it begins to storm, Blots predicts the revenge of the bugs. Paul and the Father of the house tie up Blots with wire. The radio informs the house of the escape of Felonious Bligh from Honestview Prison. Paul serves a plate of tarts and Mother dies after eating one. Blots is put on trial. Tropic of Cancer is replaced by Death in the Afternoon in lieu of a Bible. Blots is found guilty and forced to eat a tart and dies. Felonious Bligh shows up, is given a tart, and dies. Mudd calls Scotland Yard, the guest Peggy leaves, the guests Leda and Hedy state how appalled they were by Peggy’s dress and shoes. The Inspector arrives, he finds a lady-bug on Father’s shoulder, Paul offers everyone tarts, and Father sends him back into the kitchen. Then the play mercifully ends. Perhaps there was a reason it was unpublished and abandoned.

The next work, Standing on a Streetcorner: A Little Play (1953) is a stronger piece, but it is also quite disturbing. It is illustrated by Corso and was published in Evergreen Review in 1962. It is about a holy idiot watching a march of housewives and children carrying signs that say “NO SHELTERS—MORE SCHOOLS” and “NO BOMBS—MORE ALMS” on the corner of 12th Street and 6th Ave. The young man does not think the bomb will fall and the “fallout shelters are going to end up being meditation rooms, love nests …” All he wants to do is talk to people about their opinions about the bomb and help people across the street. But people are wary of him.

Whenever people dodge their way across the street, he claps in admiration because he sees them as risking their lives like bullfighters. He agrees with a barber that thinking so much about the bomb has already done irreparable damage to society. Yet he is shaken when a tall man questions the authenticity of his innocence. The play ends with the young man helping a little girl across the street: “The play might end with a car running them both down or it could end with him taking her across safely, it very well could end that way.” That shiver you just felt, the French call frisson.

Things start heating up with Sarpedon (1954), a one-act play that I wish was the first act of a three-act play. In 2016 Tough Poets Press and Schober published an edition of Sarpedon. The version published here has been corrected. According to Corso, he wrote the play in one night so that he could stay in Eliot House at Harvard. Sarpedon has died on the field of battle, but he has gone to Olympus. Hades complains. Hermes shows up speaking like a hipster. Hades goes up to Olympus and, thinking Zeus has seduced his wife Persephone in the guise of Hector, accidentally assaults Aphrodite thinking she is Hera. For those who know the story, the inside jokes leave a big smile. The play reveals Corso’s great love of The Iliad and leaves the reader wanting more.

Another gem is In This Hung-Up Age: A One-Act Farce (1954), Corso’s most accomplished play, and one it is possible to imagine being performed today. It was published in Encounter (1962), New Directions in Prose and Poetry 18 (1964), and The Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater: 1945-1985 (2010). The New Theatre Workshop performed the play in 1955 and The Harvard Crimson gave it a positive review. Corso claims it “pre-dates anything ever written about the Hipster and hip-talk,” which may be true (the term “beat” is even used a couple of times), but I would just like to add that Lord Buckley was performing his act using hipster slang in the early 1950s.

Corso’s play is an allegory that takes place on a Greyhound bus that breaks down three days out of New York heading for San Francisco. It lampoons hipsters, rednecks, liberals, struggling poets, and college students in ways that still hold up. The play ends absurdly with the bus being trampled by a stampede of buffalo, a nod to the condescending way the Native American passenger is treated by the other passengers on the bus, and the only survivor is Beauty (who does not speak), a saxophone-playing young woman zonked on sleeping pills—an appropriate survivor for the poet Corso.

JFK: A Little Verse Play (1960) is presented more like a poem than a drama. Corso put it together in Greece after hearing Kennedy’s 1960 presidential acceptance speech. It seems prophetic. Kennedy is approached by an American eagle that presents him with an egg that will reveal America’s future, all depending on how the egg is taken care of. Senator Oldhat comes in and is dismayed to find that Kennedy is more concerned with the moon and “the mystery of life” than with fighting communism.

Oldhat rushes to find Nixon to have him stop Kennedy, who is compared to a foolish Irish poet and Nero. Meanwhile, President Truman, feeling like Oedipus, laments, “I shouldn’t of done what I did.” Feeling hungry, Truman picks up the eagle egg and it hatches revealing a black shadow bird. Two years later Kennedy summons his cabinet to declare his aggressive policy against Castro. Corso proposed this play for a collection to James Laughlin at New Directions in 1962. If it was really written in 1960, could Corso truly have been this prescient? If so, it is truly remarkable.

My personal favorite in the collection, That Little Black Door on the Left (c. 1968), actually isn’t a play at all but the screenplay for a silent film that has the scent of William S. Burroughs on it like a polecat. Schober believes it was written in the mid-1960s, and he found it in Pardon Me, Sir, But Is My Eye Hurting Your Elbow? (1968). Contributors for this collection of short screenplays illustrated by cartoonist Mort Drucker of Mad included Allen Ginsberg, Bruce Jay Friedman, Herbert Gold, Philip Roth, and Terry Southern.

Using the music of the 19th century French Romantic composer Louis-Hector Berlioz’s Requiem, an apropos choice revealing something of Corso’s knowledge of classical music, the camera follows a condemned man from his last meal to the electric chair. Along the way we are introduced to a priest, a warden “who doesn’t give a damn,” and the other doomed ones who do “give a damn.” We identify with the condemned man because his “last mile” is shot from his POV “in the cliché style of the Cagney-Warner Brothers pictures of the 1930s.”

It isn’t until the condemned man is to be placed in the chair that it is revealed that he is too fat to fit in it. It turns into a surrealistic farce as several things are tried and nothing works. The fat man and the warden are reduced to tears. A carpenter is called in and, as the priest helps him, the coup de grâce of the pasquinade (a fancy word for “satire” that comes from the Italian, which I think Corso would like) comes with the priest’s Bible falling on the lever electrocuting the warden, four guards, the executioner, the carpenter, and the priest. The prisoner picks up the Bible and walks through the Little Black Door while reading it.

https://toughpoets.com/book_corso_plays.htm

GREGORY CORSO (1930-2001) was an American poet, playwright, and leading member of the Beat movement in the 1950s. He was the youngest of the inner circle of the Beat Generation writers, which included Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. He was the author of many books of poetry, including Gasoline, The Happy Birthday of Death, Elegiac American Feelings, Herald of the Autochthonic Spirit, and others. KURT HEMMER is professor of English at Harper College. He is the editor of the Encyclopedia of Beat Literature. With filmmaker Tom Knoff, he produced several award-winning documentary films on Beat poets. His essays have appeared in Naked Lunch@50: Anniversary Essays, A History of California Literature, Beat Drama, The Cambridge Companion to the Beats, and Approaches to Teaching Baraka’s Dutchman.

KURT HEMMER is professor of English at Harper College. He is the editor of the Encyclopedia of Beat Literature. With filmmaker Tom Knoff, he produced several award-winning documentary films on Beat poets. His essays have appeared in Naked Lunch@50: Anniversary Essays, A History of California Literature, Beat Drama, The Cambridge Companion to the Beats, and Approaches to Teaching Baraka’s Dutchman.