by Jim Dunn

Yours Presently: The Selected Letters of John Wieners

edited by Seth Stewart

University of New Mexico Press

In the first letter in The Selected Letters of John Wieners to his friend Robert Greene, John Wieners begins with, “Read Slow. This is a bombshell”; sage advice to his friend and an apt description of the entire collection of letters that follows. These letters are a literary bombshell of all sorts. Reading them slowly allows the reader pause to appreciate the many sides put forth in these correspondences of a brilliant, resilient, complicated poet. Allen Ginsberg’s observation in his introduction to Wieners’ Selected Poems, 1958-1984 resonated deeply while reading these letters, “He (Wieners) presents emotion on the spot—despair, love nostalgia, bliss of love dissatisfaction, flesh pressing on flesh. And Glamor… It’s thrilling to watch the drama develop.” There is a religious commitment to the act of writing from whatever emotional or physical state Wieners was experiencing at the time that transcends the challenges of his life, serving not only as his salvation, but also as his muse in his poems and as history in these letters.

In another early letter to Greene in 1955 he has premonitions of the hardships ahead and fears for a future that will come at great cost. “I think this era, is the hardest I have been through,” wrote Wieners, “as I am now totally alone, for the first time, and very nervous about the possibility of a life alone, old, drunk, etc. And yet what else can I think of when this thing is being smashed, a thing that was always warm inside me, and now it’s as if I am paid back for all that warmth. You know the old cliché, you have been too happy…the gods will punish us surely…Right now there is nothing but John Wieners and white paper, and it is killing me…”

Almost 20 years since his death, Wieners is finally receiving the attention his work deserves. His luminous body of work stands alone. His selected book of poems Supplication edited by Robert Dewhurst, CA Conrad, and Joshua Beckman allowed his work to be appreciated by a new generation of devoted followers who identify with his brave and courageous stance as a queer outsider. He was aware of the reciprocal nature of his appreciation for friends who adored him and his work. He once signed a book to a friend in true movie star style, “To my most cherished admirer.” He could also be bitingly funny. When discussing a book of poetry published by a well-known friend, his judgement was short and sweet. “I am a friend but not a fan.”

The themes tackled in Wieners’ poetry—queerness, transgender identity, gay liberation, working class values, and familial dysfunction—were ahead of his audience. His unflinching treatment of these issues in his work, coupled with his disregard for the self-promotion and publicity required for a professional poetry career, contributed to the neglect and marginalization of his work for years. Seth Stewart has worked tirelessly over a decade to correct this, taking on the task of collecting, editing, and annotating Wieners’s letters, found scattered across the country in various libraries and personal collections. Wieners was notorious for destroying or throwing away poems and letters later in his life, which made Stewart’s task even more formidable.

Stewart began his work by collecting and publishing Wieners’ correspondence with Charles Olson in Ammiel Alcalay’s Lost and Found series at CUNY. From this central relationship with Olson, the circle of connections, friends and fellow poets, swirled outward to many worlds in which Wieners was an essential force yet, ultimately, an outsider. From the first letter to college friend Greene, to Olson, Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Amiri Baraka, Diane di Prima, Joanne Kyger, Michael Rumaker, Duncan McNaughton, Anne Waldman, Joe Brainard, Irving Rosenthal, and Charley Shively, the arc and reach of his poetic connections is startlingly grand in scale. His story details the challenges and triumphs of a much loved “poet’s poet” whose vocation was a holy and sacred calling that led to early acclaim and notoriety but ultimately to tragic, darker corridors: madness, hospitalization, lost loves, familial dysfunction, and poverty.

His 1961 letter to Irving Rosenthal details Wieners heartbreaking struggle and his resilience after his forced hospitalization. “I wish I had some memory of last year, but I do not, of your kindness, but all is a blank. All I remember is waking up in the hospital, trying to get well in April, and finally after 30 shock treatments at Bournewood, and 91 insulin treatments at Metropolitan State…I am quite well: I go into Boston nearly every day, looking for work, or visiting friends…and think about my past, which is most tantalizing as I believe the shock treatments took away my memory.”

Stewart has stated that this collection of letters is the most important collection of a poet’s letters since John Keats’ letters. This may seem to be an audacious claim, but it is not too far off the mark. The revelation of these letters is the sheer vitality in his many friendships with poets and the scope of his various literary connections, allowing the reader to witness Wieners at the center of numerous literary movements post World War II—Black Mountain, Poet’s Theatre, San Francisco Renaissance, The Beats, Boston Occult School, Boston Free School, and Stone Soup among them. These correspondences not only restore Wieners to his proper place in history, but they serve as a secret history, an indispensable epistolary biography of a poet and his times. Wieners wears many hats in these letters: acolyte, gay confidante and gossip, hip friend, editor, lover, activist, movie star goddess, poet, Bostonian, and devoted friend.

The portrait of the young Wieners portrayed in the earlier letters—clear, articulate, and brilliant—reminds me of the first time I saw footage of John Wieners and Robert Duncan talking in San Francisco in Richard O. Moore’s USA:Poetry public television series. Wieners was angelic, impeccable in a white fedora and suit. He spoke with a certain measured grace. It was shocking watching this young, ambitious, and self-assured version of Wieners, realizing how much he had lost since then and how much he had given to his art. These letters give readers full view of that young energetic poet becoming, who is eagerly engaged in the essential work beyond poetry—bearing witness, making connections, building community, and establishing relationships with friends and poets—some who would remain friends until the end of his life.

Coincidentally there is a letter to Duncan from 1957, a few years earlier than when their meeting in San Francisco was filmed. Wieners gives Duncan his take on “The State of the Poem” as he gathered work for the first edition of his Measure magazine. “I think personally for you, that you/we must go where our likes in yr sense of conviction are, where we are freest formwise, where the wings can have their full spread: that is what I look for: breadth of a man’s reach, how much his eye can hold, the ‘direction of will’ so if I was to say; a lover of poetry only.”

Beyond the brilliance of the letters themselves, Stewart frames the collection with meticulous footnotes and informative sectional introductions that add depth and color to the chronological trajectory of Wieners’ narrative. The glossary of names in the appendix informs the letters nicely for those not familiar with the entire cast of addressees. It reads like a who’s who of New American Poetry of the last century. Eileen Myles’ preface thoughtfully examines the Wieners we encounter in the letters. Myles invokes a vanishing Boston “with an underbelly well equipped to hold poverty, deviant sexualities, and art” in their appreciation of the fresh portrait the letters give of Wieners as “your knowing friend. But what does he know? It there’s anything newer than John Wieners’ poems, it’s the rolling body of language they come from.”

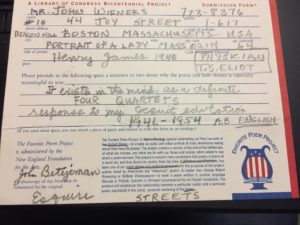

Although he didn’t write many letters later in his life, he still enjoyed receiving mail. There was one card that he displayed proudly in his apartment; it was a thank you letter from Peter Gizzi’s poetry students and it was filled with deeply personal and sincere messages of gratitude for John’s work from a new generation of readers. It was a stunning and heartfelt letter. He never mentioned it, but I could tell he was touched by it. There was also one postcard he never sent that I found tucked in a book after he passed away (pictured). It was a postcard response to Robert Pinsky’s Favorite Poem project. On the address, Wieners had collaged a small black-and-white photo over the address of a couple embracing as the man played the clarinet. On the backside he answered the questionnaire in pencil with his unique perspective, a certain humorous, surreal logic.

The later letters contain many examples of his perception of reality and glamor in his bursts of language in a dreamlike consciousness. The last letter included in the book was a Christmas card to his old friend Robin Blaser in 1997. It is touching, funny and an appropriate last letter to one of his oldest friends. “Just your two-volume edition on the works of ‘Tatum O’Neal’ and I recommend your scrupulous board direction to any, who if I remember correctly, dare broach the subject. Keep me posted on your new address. Wish I could afford iF.(sic) It’s well worth the price.” He loved the mail and kept every piece—junk mail, fliers, ads, bills, jury duty notices, postcards. Little did I know then of the holy mountain of correspondence that he had penned over the years. Thanks to Seth Stewart, many of those letters are included in this wondrous and essential collection.

JIM DUNN is the author of Soft Launch (Bootstrap Productions), Convenient Hole (Pressed Wafer), and Insects in Sex (Falling Angels Press). His work has appeared in various publications, including Bright Pink Mosquito, Gerry Mulligan, Carve, No Infinite, Shampoo, EOAGH, Polis, The Battersea Review, Blazing Stadium, and Can We Have Our Ball Back? He lives in Beverly, Mass.

Born in Boston, JOHN WIENERS was a Beat poet and member of the San Francisco Renaissance. He was also an antiwar and gay rights activist. His poetry combines candid accounts of sexual and drug-related experimentation with jazz-influenced improvisation, placing both in a lyrical structure. In an interview with his editor, Raymond Foye, Wieners stated, “I try to write the most embarrassing thing I can think of.” As Robert Creeley observed, “His poems had nothing else in mind but their own fact.”

Wieners earned a B.A. from Boston College and studied at Black Mountain College with Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, and Robert Duncan. He later followed Olson, his mentor, to SUNY Buffalo. He published his first book of poetry, The Hotel Wentley Poems, at the age of 24. Numerous collections followed, including Ace of Pentacles; Nerves; Behind the State Capitol, or Cincinnati Pike, a collection of letters, memoir, and poems; Selected Poems 1958–1984; and Cultural Affairs in Boston: Poetry & Prose 1956–1985.

Wieners’ honors include awards from the Poets Foundation, the New Hope Foundations, and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, as well as a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He founded and edited the literary magazine Measure (1957–1962). Wieners also worked as an actor and stage manager at the Poet’s Theater in Cambridge, Mass., and taught at the Beacon Hill Free School in Boston.

An edited notebook of his poetry and prose, The Journal of John Wieners, is to be called 707 Scott Street for Billie Holiday, 1959, was published in 1996, and another notebook, from 1971, was published in 2007 as A Book of Prophecies. His papers are collected at the University of Delaware and the University of Connecticut. He spent the last 30 years of his life in Boston.

John Wieners bio from Poetry Foundation.