by Alex Emanuel

It happens every spring, baseball that is, our National Pastime. For a while there the nation wasn’t sure if baseball would be happening this spring, however, and with everything else that’s happening these days what would or wouldn’t be on the diamond seemed pretty trivial anyway. Thankfully, though, after what seemed like endless negotiations between the powers and players that be, the season is happening (larger bases, universal DH, and expanded playoffs be damned), and the nation once again will have that pleasant summer distraction so many of us eagerly await as soon as the last pitch of the previous year’s World Series has been thrown.

It happens every spring, baseball that is, our National Pastime. For a while there the nation wasn’t sure if baseball would be happening this spring, however, and with everything else that’s happening these days what would or wouldn’t be on the diamond seemed pretty trivial anyway. Thankfully, though, after what seemed like endless negotiations between the powers and players that be, the season is happening (larger bases, universal DH, and expanded playoffs be damned), and the nation once again will have that pleasant summer distraction so many of us eagerly await as soon as the last pitch of the previous year’s World Series has been thrown.

It Happens Every Spring was also the name of a screwball comedy with Ray Milland from 1949 that my father saw when he was a kid and made me aware of many years later. In the film, this college science professor, played by Milland, accidentally invents a chemical that, when applied to an object, repels wood. You can imagine then what happens to a baseball when it gets near a bat coated with the stuff. The professor realizes the elusive possibilities, takes a leave of absence from his job (and his senses), tries out for an MLB team and voila… rockets to success overnight, all thanks to his juiced screwball.

He eventually ditches the game and fame after the compound runs out and before his head becomes as big as Roger Clemens’. Despite the ethical questions raised by this film, toeing its flubber rubber, I saw instantly why my father, known for his wild imagination and enduring childlike curiosity, would dig it, maligned by critics as it was. It’s fun.

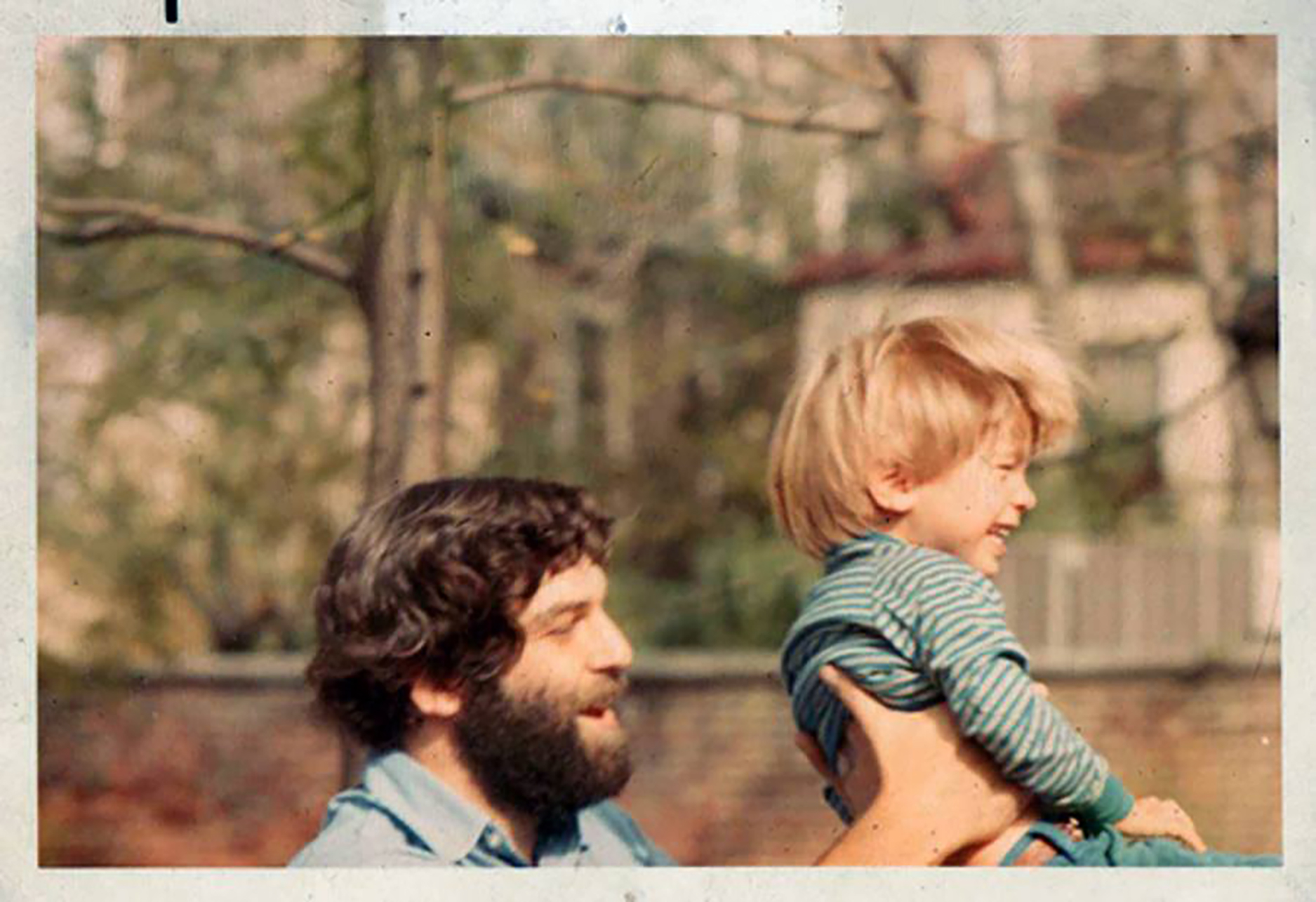

He and I bonded on the movie as we did so many things. We had a similar sense of humor and dreamed about baseball as kids while opting for careers in the arts. No “sabermetrics” were involved in our respective decisions. Acting, music (and later filmmaking and playwriting) chose me (though I chose to go by my middle name as my last instead of my father’s suggestion of Milland after I got out of school and found there already was an Alex Grossman treading the boards), while my Dad merely changed the world of commercial art with his airbrush, hitting a grand slam as a cartoonist, illustrator, animator, and, finally, graphic novelist, in a Hall of Fame career that spanned over 50 years.

He and I bonded on the movie as we did so many things. We had a similar sense of humor and dreamed about baseball as kids while opting for careers in the arts. No “sabermetrics” were involved in our respective decisions. Acting, music (and later filmmaking and playwriting) chose me (though I chose to go by my middle name as my last instead of my father’s suggestion of Milland after I got out of school and found there already was an Alex Grossman treading the boards), while my Dad merely changed the world of commercial art with his airbrush, hitting a grand slam as a cartoonist, illustrator, animator, and, finally, graphic novelist, in a Hall of Fame career that spanned over 50 years.

Every spring when MLB players go to camp I think about that kooky film with Ray Milland, and about my father, Robert Grossman. When I mention his name to people who didn’t know him, their eyes light up as soon as I say he did the poster for the movie Airplane!. My father was also known for his iconic album cover art, political caricature work and over 500 magazine covers, for the likes of Time, Rolling Stone, Newsweek, New York Magazine, National Lampoon, The Nation, The New York Times, Forbes and… the list goes on and on.

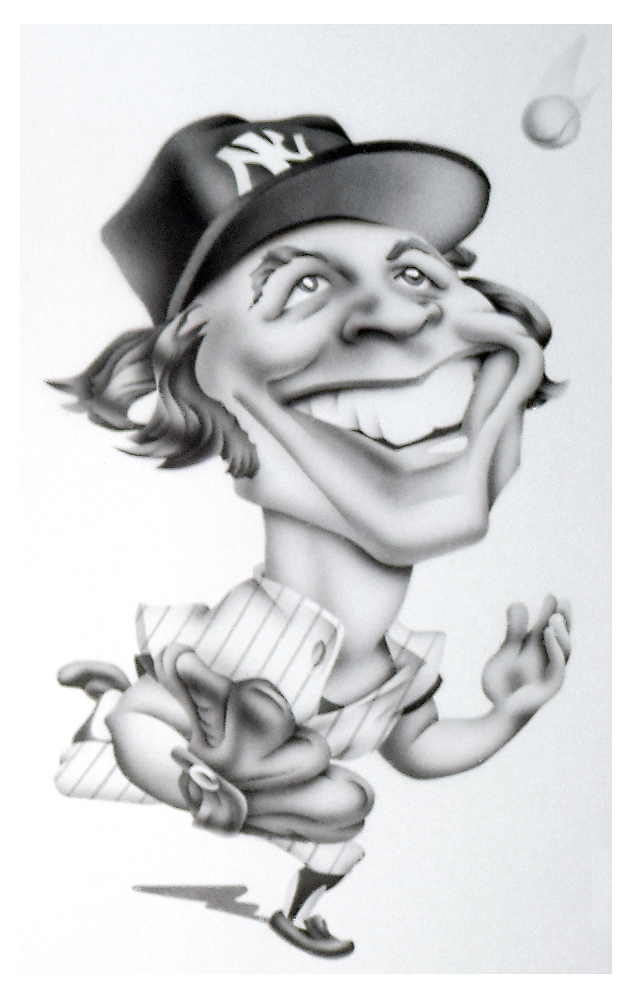

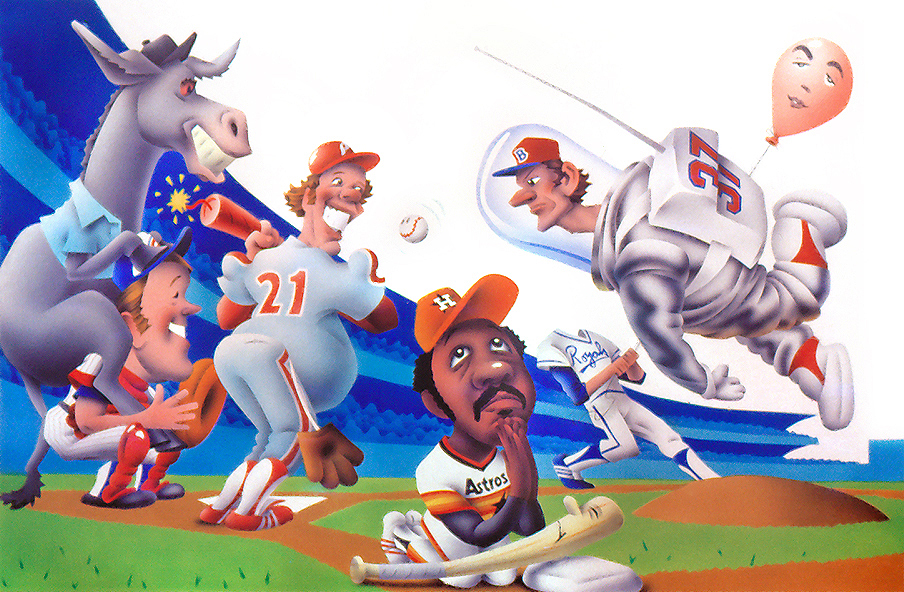

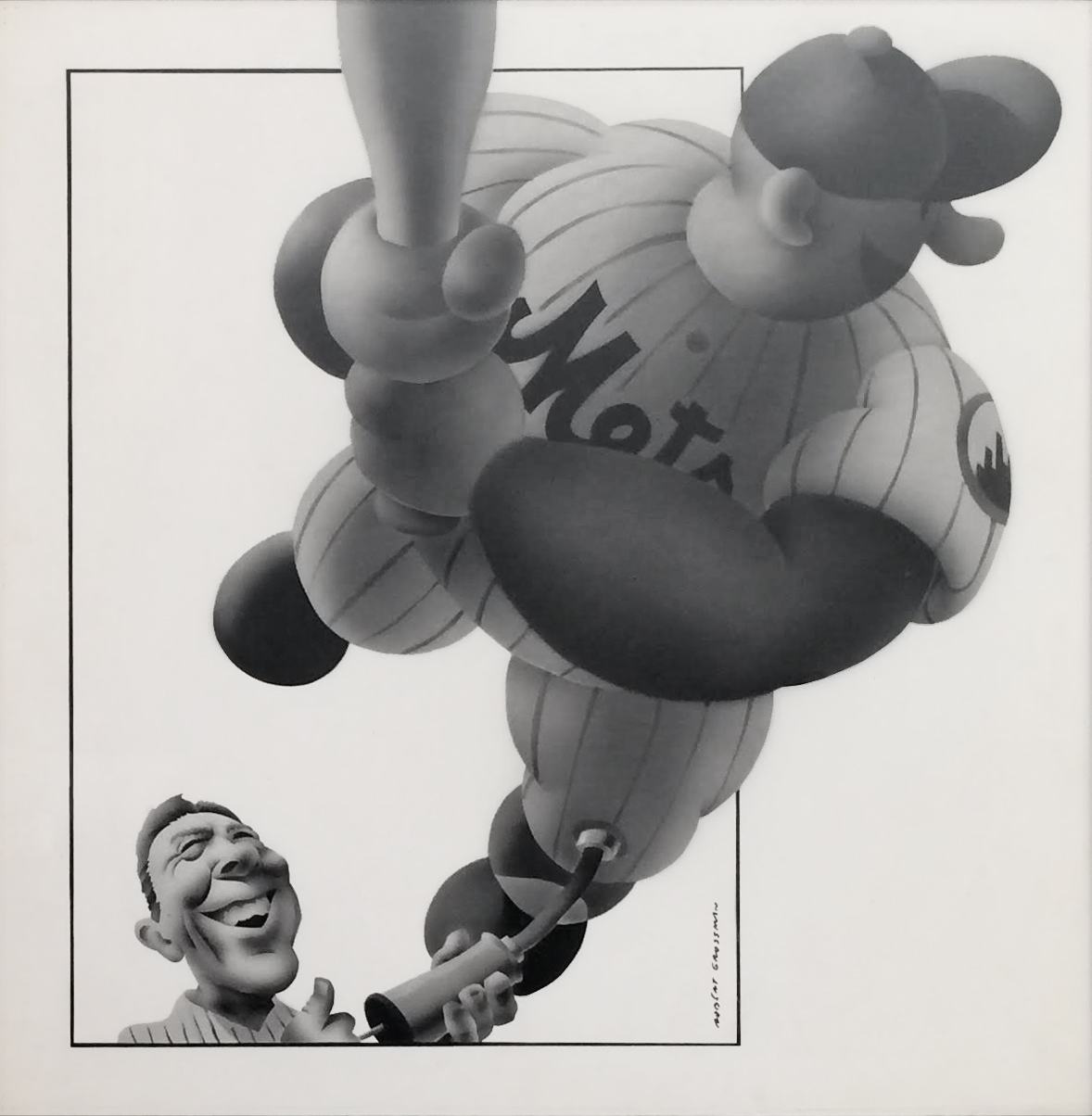

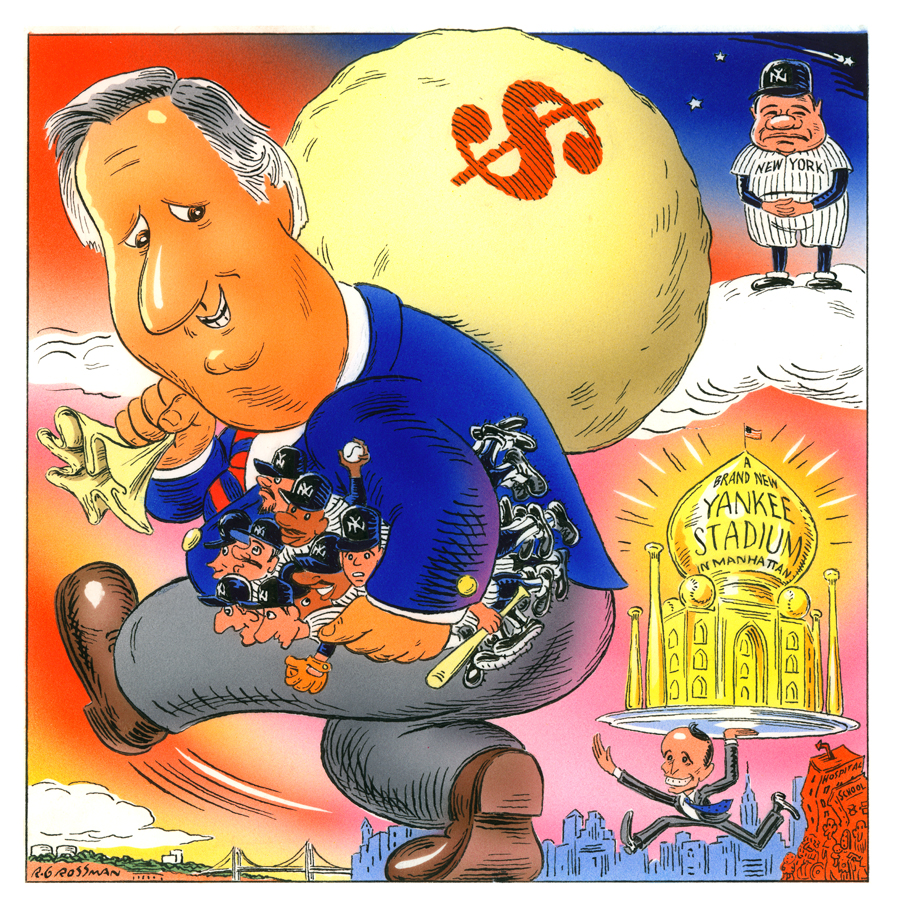

As ubiquitous as his work was my dad said he liked to “illustrate the unillustratable,” and when asked what his quintessential illustration was, he responded that he “was so thoroughly permeated with the quintessence that it emerges in whatever I do,” which also included a lot of baseball-related work, for Sports Illustrated and other publications. Many of those pieces, some of which you see here, I’ve enjoyed sharing with friends on opening day over the years.

You see, I’m a diehard baseball fan, for better or for worse, have been ever since my father took me and my friends to Mets games at Shea when I was a little kid in NYC and then later Red Sox games at Fenway Park when we moved to Western Mass. While my father didn’t share the same fandom as me, that was only because the sport was a complicated subject for him. He too had a childhood passion for the game, that is until his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers moved out west and broke his and neighboring kids’ hearts.

You see, I’m a diehard baseball fan, for better or for worse, have been ever since my father took me and my friends to Mets games at Shea when I was a little kid in NYC and then later Red Sox games at Fenway Park when we moved to Western Mass. While my father didn’t share the same fandom as me, that was only because the sport was a complicated subject for him. He too had a childhood passion for the game, that is until his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers moved out west and broke his and neighboring kids’ hearts.

But even though he stopped watching, it didn’t stop him from fostering that same passion in me. He encouraged it, in many ways living vicariously through me right up until he passed away unexpectedly in March of 2018. In NYC my dad sent me to an after-school program called Shelley’s All-Stars, run by a former Pittsburgh Pirates’ coach, and in Massachusetts, little league, and he beamed with joy that I was playing softball well into my adult years, telling me how happy that made him, and he’d often ask me how the Sox and Mets were doing. He also suggested to me, many times over the years, that I recite Casey at the Bat as a one-man show, being I was an actor and baseball junky. I always declined, but in retrospect I wish I’d taken him up on that suggestion as he would’ve been so pleased.

After my father passed there was a void. I’d lost a father and a pal. I tried my best to fill it by going through all his work and memorabilia he’d left behind. It kept me close to him. I was fascinated by the amount of sketches and correspondence he’d saved and pieces I’d never seen, and I became determined to know even more about him than I already did. I’d been shooting him sporadically with my iphone since my mother passed away in 2013, and after showing a 15 minute film I’d cobbled together of him and his work at his memorial I was encouraged by friends of his and mine to do a documentary project about him. I took them up on it, and will be doing a crowdfunding campaign for it this coming May.

After my father passed there was a void. I’d lost a father and a pal. I tried my best to fill it by going through all his work and memorabilia he’d left behind. It kept me close to him. I was fascinated by the amount of sketches and correspondence he’d saved and pieces I’d never seen, and I became determined to know even more about him than I already did. I’d been shooting him sporadically with my iphone since my mother passed away in 2013, and after showing a 15 minute film I’d cobbled together of him and his work at his memorial I was encouraged by friends of his and mine to do a documentary project about him. I took them up on it, and will be doing a crowdfunding campaign for it this coming May.

Here’s the thing, my father was not only a seminal artist, with a nimble wit to match his abundant draftsmanship, he was “that guy”; charismatic, well-loved and admired by many. People glow when they talk about him to me. He took a real interest in not only his work and family, but in everything and everyone, while all the time remaining humble. When Yogi Bera died, I asked my father if he’d ever drawn him, his reply was “Alas for Yogi, he was matchless. No, I never drew his picture, but that’s just one aspect of the charmed life he led.”

What was most important to him was that he’d been able to make a living doing the thing he loved doing most when he was a kid, a sentiment we’ve often heard shared by baseball players and other professional athletes. He was forever grateful, saying “it’s a wonderful privilege to be able to do the stuff that you’ve done since the age of 3 and raise a family.” He was generous to a fault, believing we were put on this Earth to serve, and his job was to serve up humor.

But he was not only funny, he was the smartest person I knew, and a hero to me and others. One time I remember when I was a kid playing running bases on the street with friends outside of his studio in Little Italy, he even acted the hero. Some bigger kids had ridden up on their bikes and were pushing us, trying to steal our mitts when my pops burst onto the scene waving a baseball bat, telling the child-bullies he’d make contact if they didn’t shove off. Needless to say, they made like Ricky Henderson and were gone in a flash. Like the balloon-shaped 3-D airbrush renderings my father was known for he could be larger than life at times, even larger than the 6’4” he already was.

But he was not only funny, he was the smartest person I knew, and a hero to me and others. One time I remember when I was a kid playing running bases on the street with friends outside of his studio in Little Italy, he even acted the hero. Some bigger kids had ridden up on their bikes and were pushing us, trying to steal our mitts when my pops burst onto the scene waving a baseball bat, telling the child-bullies he’d make contact if they didn’t shove off. Needless to say, they made like Ricky Henderson and were gone in a flash. Like the balloon-shaped 3-D airbrush renderings my father was known for he could be larger than life at times, even larger than the 6’4” he already was.

The pandemic slowed my documentary drive some, but I’ve managed to do interviews here and there and collect an abundance of material along the way. I’m not only hoping to realize my film homage to my father, but I’m also planning for the crowdfunding I do to go toward a long-overdue retrospective book of his work. In it there will surely be a section devoted to his Sports illustrations.

In going through the vast archive he left behind, I found, among other things, many baseball-themed items, including some marker sketches he did for me years back of Joe Rudi and Cesar Geronimo, and childhood drawings of an on-field brawl and his take on Willard Mullin’s “Dem Bum” Dodger Mascot. He also saved a baseball underground comic I made when I was 11 that he printed hundreds of copies of, and a couple airbrush caricatures of Rollie Fingers and Chris Chamblis I did under his tutelage. I’ve also transferred over 50 super 8, 16mm films and sound recordings he and my grandfather made that turned up. Among them I found footage of Ebbets Field and our first trip to Fenway. I also uncovered a recording of him reciting Ernest Thayer’s ballad of “mighty Casey” when he was 13… had I only known he learned it at such an early age. Hearing my deep-voiced dad reciting the poem in a pitchy Brooklynese-tinged pre-pubescent voice was priceless.

So, I hope you enjoy the selection I’ve chosen here of some of my favorite baseball illustrations by my father, pieces that span a lifetime of work. To learn more about him and see more of his work please visit robertgrossman.com. If you’d like to know more about the Robert Grossman documentary and/or are interested in donating/making a contribution, please like and follow him on Facebook at facebook.com/robertgrossmanart, and on Instagram @robertgrossmanart. There I’ll be posting updates about the project, as well as news about the retrospective book, any potential future retrospective shows, and of course, lots of classic Robert Grossman art. Lastly, with the baseball season upon us, I want to leave you with a little thing my father wrote about fans like me. While he didn’t invent a chemical that changes the direction of a baseball, he did happen to invent… the “rooton.”

So, I hope you enjoy the selection I’ve chosen here of some of my favorite baseball illustrations by my father, pieces that span a lifetime of work. To learn more about him and see more of his work please visit robertgrossman.com. If you’d like to know more about the Robert Grossman documentary and/or are interested in donating/making a contribution, please like and follow him on Facebook at facebook.com/robertgrossmanart, and on Instagram @robertgrossmanart. There I’ll be posting updates about the project, as well as news about the retrospective book, any potential future retrospective shows, and of course, lots of classic Robert Grossman art. Lastly, with the baseball season upon us, I want to leave you with a little thing my father wrote about fans like me. While he didn’t invent a chemical that changes the direction of a baseball, he did happen to invent… the “rooton.”

____________________________________________________________

How Rooting Works

by Robert Grossman

Not everyone is a rooter—a person who cares enough about an athletic contest to root for this or that contestant to win. In fact, the ability to root successfully is not evenly distributed in the population. But, regarding the rooters who find their rooting rewarded, one cannot help but wonder how they do it.

Not everyone is a rooter—a person who cares enough about an athletic contest to root for this or that contestant to win. In fact, the ability to root successfully is not evenly distributed in the population. But, regarding the rooters who find their rooting rewarded, one cannot help but wonder how they do it.

Now science has an answer. The mind and body of a rooter produces a subatomic particle called the “rooton.” Rootons pass through the air or through wires or optical fibers into the minds and bodies of athletes producing the extraordinary mental and physical feats required for winning.

Rootons have the capacity to penetrate the well-known “luck field” surrounding contests of any kind. Rootons also have a tendency to be attracted to uniforms. So, when a team or an individual triumphs it is due to the barrage of rootons that brings it about.

The ability to root is confined to human beings, with the only exception being certain gifted swine who’s rooting produces only truffles. Rooting is often mistaken for mere “hoping,” which, as anybody knows, is a hopeless endeavor, and Rootons must not be confused with “croutons”—a fundamental particle that mysteriously finds its way into soup.

Play ball!

All pictures ©robertgrossman __________________________________________________________

ROBERT GROSSMAN

ROBERT GROSSMAN

To learn more about the documentary and/or donate/contribute,

please like and follow

https://www.facebook.com/robertgrossmanart

https://www.instagram.com/robertgrossmanart

ALEX EMANUEL

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1218566/

https://alexemanuel.bandcamp.com/

#the_alexemanuel

SAG-AFTRA, AEA Actor. Writer. Musician. Filmmaker. Producer. Director. Artist.