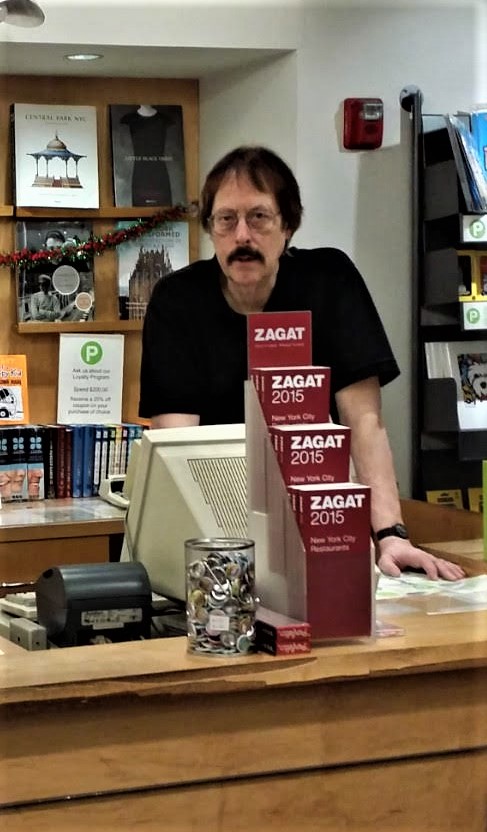

Ron Kolm working at Posman Books in Grand Central, which closed years ago.

Sarah Sarai poses a few questions to the archivist of the downtown poets and activist for literature.

Boog City:

You are from Pennsylvania, that hotbed and mixed bag of American history. Artists from Pennsylvania include Warhol, Toi Derricotte, Wallace Stevens, Willa Cather, Terrance Hayes; many others. What do you carry with you from growing up there? What brought your folks there and why’d you leave?

Ron Kolm:

My father was an engineer who helped design the B-29, which dropped atom bombs on Japan at the end of WWII. He worked for Boeing in Seattle, then moved to Pittsburgh to help design landing craft. He ended up becoming the chief engineer of the Delaware River Port Authority, and that’s why my family ended up in Flourtown, Penn. He had the final say as far as repairs on the Benjamin Franklin Bridge were concerned.

After VISTA ended, we moved to New York City. During the winter of my discontent in Appalachia I spent hours writing and, figuring that all real writers seemed to eventually live in, or pass through, NYC, we decided to head in that direction. I had read a ton of Pennsylvanian writers in college: John Updike, John O’Hara, among them, but the one who influenced me the most was Ezra Pound. Every poet should be required to read his book, The ABC of Reading. It’s a terrific roadmap to better writing.

You’ve mentioned that your sister is/was a minister. I’m a fan of belief, despite having a Christian Scientist for a mother. Without asking if you “believe,” which is none of my business and also simplistic, I dare to ask if (and how) both traditional and our generation’s hippie spiritualism figure into your life.

I’ll answer that as best I can. I’ve always tried to analyze what happened in America from my own perspective: from the conformity of the ’50s to the countercultural reaction of the ’60s and ’70s. It all boils down to a war: Vietnam. In the ’50s I would go to a neighborhood bank with my father every Friday night and marvel at all the stiff white men dressed in suits with their close-cropped hair playing with their money. None of them smiled or talked to anyone else—to me, they were all zombies. During my college years, as the war unfolded, I watched as folks grew their hair long and discovered drugs. The Beats were in vogue, and demonstrations against the war finally ensued.

To answer your question, I guess this is when I became a humanist. I’m not particularly openly religious, but during this period of doing drugs there was one moment that etched itself in my mind forever. I was looking out a window at a cloudy sky, utterly stoned, and it hit me in a flash that the universe has a dark sense of humor. I continue to marvel at this dark humor whenever impossible coincidences occur in my life, or to others, and it is those moments I try to capture in my poetry and prose.

My poem “Corpses and Cats” is about the siege of Leningrad. It sprang from a bio I’d read of Shostakovich—all of which I said at the Parkside while on stage. You shouted I should read his memoirs. Which is to say: I have noted you are a voracious reader. When did this splendid affliction first show? Were there other readers in your childhood and adolescence and how did they influence you (or not)?

I was a lonely kid, trapped in my bedroom in my parents’ suburban house after coming home from school every day. The only thing I could do to fill all the dead time was read. I worked my way through the family library, and then through the books I would find during Boy Scout paper drives. Because I was lonely and introverted, most of the stuff I read involved war—I can still tell you everything you’d never want to know about WWI and WWII.

Idiotic though we may be, most poets I run across fantasize some fame. Is that part of the creative impulse? If it’s not too probing, is it an engine of your indefatigable energy? (Sensitive Skin; the Unbearables; your archives; your poems and fiction.) If not, any idea what drives you?

In all honesty, I do think about this, and I guess I would answer thusly (and this is a great question!). Given all the stuff that’s been written during the course of human history, why has only some of it lasted? In fact, only a very small portion goes forward through time. I feel sort of blessed to be swimming in this river, and I try to keep my head above the waves. I do feel that my job is to try to give back something for what I’ve gotten. Literature liberated me from a death-in-life existence, and I am grateful for that. And I guess my self-definition is more than a little wrapped around how my work is received. Sure, to some degree or another I do live through my oeuvre.

The Fales Library at NYU houses the Ron Kolm Papers—35+ cartons of books, letters, objects. Where did you store all this before? What led you to archive the downtown poets of NYC?

I have to admit that I’m an anal retentive, so collecting things is what I do. I collect decks of cards, especially the aces. I also collect foreign film dvds—I have complete runs of Bunuel, Godard, Truffaut, Kurosawa, Fellini, Bergman, etc., so collecting all the works by the authors I love was a no-brainer.

When I moved to the city I made my way to Schocken Books, the publisher of Franz Kafka, and bought a set of his books in hardcover. I have runs of Beckett, Joyce, Anne Sexton—you name it. So, as a true anal retentive who was already hooked on collecting books, I lucked out and got a job in the Strand Bookstore. When that ended rather abruptly, the only job I could find was at Eastside Bookstore, in the heart of the East Village. It didn’t take me long to discover how culturally rich this somewhat abandoned neighborhood was. There was ABC No Rio, CBGBs, and a ton of self-produced zines and chapbooks. I was pretty sure that no one else was collecting this stuff, so I dug in with gusto. I ended up with so much material in my tiny apartment you could barely see out of the windows if you looked over the boxes of stuff on tiptoes.

As far as the Fales goes, that happened because Marvin Taylor became the head librarian and found out about my collection from the reviewer Vince Passaro, and got in touch with me. I also had been written up in The New York Times for all the crap that was in my apartment. I have built and continue to feed other archives as well: SUNY Buffalo, the main branch of the N.Y. Public Library on 42nd Street, The Harry Ransom Center in Texas, and Rochester University.

I don’t know that things are “worse” than ever before—the country began by thieving, shackling, and murdering. But they ain’t good. What do you see as the flaw, in the U.S. or humans, in general?

Another great question, which I do think about almost continuously. I have this notion that human nature hasn’t changed a jot since the beginning of humankind. The same amount of good and bad exist, or co-exist, with each other down through time. I think the Greeks felt that there was a balance between good and evil—Thanatos and Eros—death and life. I tell my friends to try to add to the Eros side as best they can, because so many folks are tossing stuff onto the other side.

Of course population growth is exponential, and climate change might wipe us all out. The other great problem that follows us down through history is the terrible treatment of women by men, which is unforgivable. I fear the violence that so many males seem to internalize, and then act out—I read about this in the books on warfare I collected—and it scares me to this day. I can still hope for a better day, and that is why I write.

Ron Kolm is a writer, bookseller, publisher, and more. He earned two degrees in history and channeled his historical bent to documenting New York City’s downtown poetry scene by collecting posters, small press and hand-made artifacts, and other downtown-alia. His archives were purchased by NYU’s Fales Library. Ron is author of The Plastic Factory, Welcome to the Barbecue, Divine Comedy, and many other books; editor of several anthologies; co-organizer of the downtown poetry collective, Unbearables. He lives in Astoria with his wife and two sons.

Sar ah Sarai is the author of the poetry collections That Strapless Bra in Heaven (Kelsay), Geographies of Soul and Taffeta (Indolent), and The Future Is Happy (BlazeVOX) [books]. She fell weirdly in love with her first Barbie doll. Sarah lives in Manhattan.

ah Sarai is the author of the poetry collections That Strapless Bra in Heaven (Kelsay), Geographies of Soul and Taffeta (Indolent), and The Future Is Happy (BlazeVOX) [books]. She fell weirdly in love with her first Barbie doll. Sarah lives in Manhattan.