by Paul Vogel

Consider this a provisional attempt at paying tribute to visual poet, artist, collagist, and essayist David Baptiste Chirot. David’s Wisconsin friends Tom Hibbard, Matthew Rethaber, Zack Pieper, and I are sorting through boxes of art and reaching out to those who knew him. For now, the world still has Geof Huth’s exemplary piece from 2005, “There is Nothing but Sunlight and Shadow in the Open Street.” There is a feature in Jacket2 by Jerome Rothenberg (jacket2.org/commentary/david-baptiste-chirot), and his work is featured in numerous anthologies. Look it all up, obviously, but don’t limit yourself to Google. David’s work spans the nether regions of the internet, and were it not for resources like the Wayback Machine digital archive, it might vanish forever. I fear much of it already has.

The artist-networks David was involved in are too numerous to list. They span the globe, though some have vanished entirely. Luckily, scholarship has brought renewed attention to the worlds of mail art and visual poetry he was a part of. If one looks at a Big Chart of Twentieth-Century Cultural History, they might recognize names like Charles Olson, Bob Cobbing, and Ray Johnson. David’s name appears somewhere in that nexus.

The artist-networks David was involved in are too numerous to list. They span the globe, though some have vanished entirely. Luckily, scholarship has brought renewed attention to the worlds of mail art and visual poetry he was a part of. If one looks at a Big Chart of Twentieth-Century Cultural History, they might recognize names like Charles Olson, Bob Cobbing, and Ray Johnson. David’s name appears somewhere in that nexus.

What they all shared was a commitment to correspondence. David spent much of his life writing letters. When the internet came along, he became even more immersed in the worlds of visual poetry and experimental writing. Time becomes obscured in virtual realms, where one’s field becomes simultaneously autonomous and collective, amplified and accelerated.

David’s early online engagement coincided with his immersion in the detritus and symbols of the streets. This became the primary material of his work: scraps, tickets, various rubbings, and tracings. The obsessive quality of his work often seems like a way to get beyond writing, to something deeper, rubbing down both into it and through it. You could dismiss this as a performative intensity, but it was just one of a host of obsessive traits.

This complicates a designation applied to David, by others and himself, as an “outsider artist.” Yes, he lived with severe depression, addiction, and poverty, a life that might be reduced to the cliche of the destitute romantic genius. Zack reminds me that David saw himself in line with the role of the “poete maudit,” a mythos spanning Baudelaire and Rimbaud, to the Beats and New American poets. To me, that he was and was not an outsider makes him more interesting.

He came to Milwaukee to do a Ph.D. in the Modern Studies program during its heyday (the late ‘80s and early ‘90s) and studied with folks like Jane Gallop and Herb Blau. From an early age he had immersed himself in art and literature, and yet, like so many, was derailed by life. The remarkable thing is how productive he was despite all of that. He lived and breathed art. He carried so many forgotten names.

As we waded through his possessions in his modest apartment, one of 180 identically built one-bedroom units inside a 19-story subsidized housing silo overlooking the Milwaukee River—I looked out his third-floor window. He had a nice view of the river. If you ever want to visit the building, it is remarkably easy to break into. The residents are primarily old, poor, and extremely vulnerable, yet the surrounding area is peacefully sylvan. David felt lucky to be there. As Matthew and I rode the elevator down with yet another cart full of junk, a woman asked if we were David’s sons. When Matthew explained we were friends, adding “David had a lot of friends,” the woman replied, “David was a nut!” I think he liked his neighbors, too.

We looked for things worth holding onto—artwork, letters from friends and books, mostly. This task was complicated by the fact that David was a hoarder and a consumer of vast quantities of cigarettes, prescription pills, energy drinks, and chips. Mixed in with the garbage we found xerox copies, posters, stamps, crayons, stickers, newspaper clippings, comic books, postcards, magazine ads, exotic napkins, rare DVDs, zines, chapbooks, CDs, cassettes, photographs, records, and clothes, most of which we threw out because they were already destroyed.

When I came across younger pictures of David, I was struck by how handsome he was, how strong he looked. It’s easier now to imagine him like this. The David I knew was incredibly frail, got around on a walker, and seemed forever on the verge of total collapse. His stare was intense every time I saw him, and it’s there in those pictures, on the face of a young man.

Besides his penetrating stare, his handshake was powerful. That’s why he lived for as long as he did, I think. The whole project, if you can reduce life to such a thing, was to live with intensity. Not to be intense every second of your life like a speed addict, but to manage it, or harness it toward something less destructive, an outlet. David lived his life at various times, on the streets, in shelters, hospitals, clinics, and half-way houses, while writing countless letters, emails, asemic poems, as well as making his numerous drawings, collages, rubbings, and zines. The obsessiveness goes beyond any romantic cliche.

Before I knew who he was, David was the old punk in a leather jacket I would see in my alley, making what I later came to know as his “rubBEings” against telephone poles and other parts of the environs. Sometimes he was at poetry events or riding the bus. He was a small guy but he stood out.

Zack Pieper remembers his long-time friend, whom he met in his early 20s, as a “talker.”

“We’d walk around the parks and alleys and talk about books and movies and music and French poetry and so on. Even when his life was most dire, David was full of humor, stories (touring with Don Cherry, various capers as a music writer in Boston), and a deep knowledge on a wide range of subjects both cultural and political. As his work developed throughout the late ’90s, he became more recognized within the realm of visual poetry and mail art, nationally and internationally. He was also an active presence on the Buffalo listserv during this period; his missives often inspired beyond the confines of grammar, and sometimes wiley, or irascible in their provocations and commentaries. He hated all power structures; visible and invisible, political and social. He cared about people, especially those no one else did, and his concerns in life narrowed to almost nothing but art, conversation, and his neighbors.”

One day he got on the number 10 bus near downtown carrying a bunch of bags and sat down to read a book by Araki Yasusada. “Hi David, my name is Paul Vogel. I’m friends with James Liddy, Zack Pieper, and Mike Hauser.” That’s how I place myself within an associative network for someone who might wonder why I’m suddenly talking to them. He gripped my hand like he was going to fall over, even though he was sitting, and stared directly into my eyes. “Hey, Man! Nice to meet you! I love all of those people! Paul is my brother’s name!”

I tried to interview him once, three years ago, and quickly realized how pointless a transcription would be. David would begin one topic after another, never finish, then quickly change gears. One minute he was talking about Cobbing, the next he was talking about burning cop cars in France. He had a lot to say about the legendary Modern Studies program at UW-Milwaukee. Theory was all the rage then, and smart young literature students who could read Lacan and Derrida were brought in from around the country.

“I first met David Baptiste Chirot around 1988 when he was a graduate teaching assistant in the English Department at UW-Milwaukee where I was an adjunct,” says poet Jim Chapson. “We shared a small windowless office on the fifth floor of Curtin Hall.

“David had a fellowship in the Center for 20th Century Studies, a prestigious and selective program which at that time housed a constellation of luminaries in the then-dominant field of literary theory; among the faculty were Ihab Hassan, Jane Gallop, Herbert Blau, Kathleen Woodward, and Michel Benamou. David seemed a bit out of place among this tribe which reeked of success. He had a sort of hoodlum appearance, wearing black Levi’s and a black leather jacket with something painted crudely in white letters on the back—was it DERRIDA? In contrast to his appearance, his manner was quiet, polite, and respectful, almost timid.

“After completing his M.A., he disappeared from the campus, and I wasn’t surprised to hear he had dropped out of the doctoral program. In retrospect, I can see that while certainly meeting the intellectual expectations of the Center, David had an innocence, a guilelessness, which would preclude him from an academic career. However, I continued to see him occasionally on the 30 bus which went to Milwaukee’s east side. As years went by, his appearance changed: he became gaunt, haggard, scruffy, with a mouth full of rotting teeth; but he was friendly as always, and talkative: he knew far more than I did about the contemporary literary scene.

“Then I didn’t see David for a couple of years, and when I did his appearance had changed once more: he now looked healthy, with clear eyes, and, most noticeably, a full set of brand new disturbingly shark-like teeth.

“He performed regularly in poetry readings at Woodland Pattern bookstore, in ways predictably unpredictable. Once he stood at the mic making loud guttural sounds to a baffled Midwestern audience unfamiliar with the avant-garde tradition of sound poetry. Another time, he read a poem about the victims of Hiroshima, with his head and body wrapped in red-smeared bandages.

“In his last years he turned more to visual art. I recall seeing him crouched under a hedge making a rubbing of the inscriptions on a sewer pipe, intent as an archeologist copying Sumerian tablets. David lived in a world of obscure signs which it was his life’s work to interpret and reveal, and he did so, without encouragement or support from any institution, with dedication, and without compromise.”

I gave up my interview after about 15 minutes and asked if he wanted to go outside. We walked a few blocks to a mailbox on Brady Street as I listened. He went off on everything; from problems with his social worker and the various bureaucracies he had to navigate, to conspiracy theories and various musicians. He stopped to rummage through a dumpster. We later ran into an old friend of his who seemed even worse off. I don’t remember his name, but he was friendly and spoke to us about his faith in Jesus and a recent visit to the Poetry Center of Chicago. David gave him a couple cigarettes and the man gave David some packets of cologne. “Hey man, this stuff is really great! Thank you!”

I’m grateful I had a chance to reconnect with David earlier this summer. He’d gone off the radar again and it took some time before we were able to track him down. Tom was notified he was in the hospital and later managed to get David settled back into his apartment. When he returned he no longer had the internet. I gave him an old laptop but the building’s wifi was too weak. Zack and I brought him a TV and came back a few days later to help him when the remote stopped working. I imagine he spent much of his time in bed, watching PBS. He’d been given a smart phone, which he could barely use. When I looked at it, there were numerous missed calls, texts, and voicemails. David didn’t have his passwords for his email or Facebook account, so he was locked out of that world as well. It hurts to imagine the loneliness of that place, though I knew he could manage loneliness, like he did everything else. He’d be ok. A few weeks later, as I swept under his empty bed, I found a CD I liked, Hüsker Dü’s New Day Rising.

Boog City readers interested in contributing a one- or two-sentence anecdote to help collectively memorialize David Baptiste Chirot should write to pbvogel2@gmail.com.

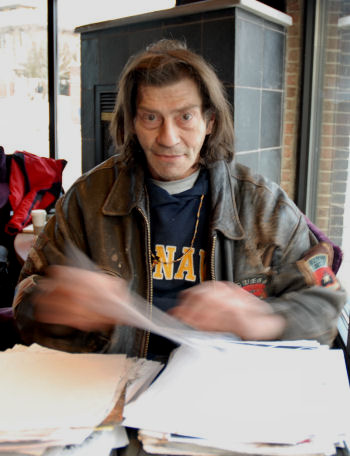

David Baptiste Chirot by Allen Bukoff.

DAVID BAPTISTE CHIROT (1953-2021) was a poet associated with visual poetry and mail art networks. Raised in Vermont, he moved to Milwaukee in 1989.

PAUL VOGEL is a Ph.D. student at SUNY Buffalo.

PAUL VOGEL is a Ph.D. student at SUNY Buffalo.