by Peter Valente

It Wasn’t Supposed to Be Like This

Greg Masters

Crony Books

My copy of Tom Savage’s Housing, Preservation, & Development (Cheap Review Press, 1988) is inscribed to the poet Rose Lesniak, “A rose who has no thorns.” Anyone remember her? or Barbara Barg? or Susan Cataldo or Michael Scholnick or Tom Weigel or Rene Ricard? And if so, ask yourself how well known is their work these days among the younger poets. And what about Savage or Harris Schiff? They should be better known but institutions of poetry have their own special agendas with regard to certain movements and poets, with the academics, furthermore, often framing arguments from a privileged perspective and not from the level of the street. For Amiri Baraka this is “playing it safe,” not “‘saying something’,” in order “to protect one’s career,” for example. The danger, Baraka writes, is that this “creates a pervasive dullness, an entropy of the speeds of poetries involved with an actual which includes war, being of it or opposed to it.”

•

Ted Berrigan, writes poet Joel Lewis, “would never put down other poets … Even poets that we considered, in our hyper-critical youth-o-scope, to be square and beyond our pale, Ted would firmly insist: “‘Hey, he’s a real poet.’” The process of inclusion and canonization today is revealed, for example, in each new Norton Anthology. The net reaches as far as it can go and other anthologies reach still farther and are more inclusive than Norton, and perhaps more accurate in their attempts to encompass the various poetry movements as they attempt to establish a coherent history up to the present. But they don’t, nor can they, reach far enough. It is always a provisional selection. As Alan Davies once put it, “Anthologies are to poets what zoos are to animals.” What is necessary now more than ever is a kind of research and development work because what makes the news is never the entire story or even, in many cases, what is most important.

•

Greg Masters’ It Wasn’t Supposed to be Like This is just such a kind of book. In his long poem, “My East Village,” he paints a portrait of the changing landscape of the Lower East Side, including his own initiation into the world of the poets surrounding The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s. He writes about meeting Ted Berrigan, “propped up in bed/ like a downtown maharajah/ welcoming visitors to the/ digs he shared with Alice Notley / a poet not much older than/ us.” Or Bernadette Mayer and Lewis Warsh, where he “blended into their household/ as if there were no barriers/ and would for the next several/ years be a regular presence/ amid the routine proceedings/ of the day, which in their system/ was nothing like ordinary.”

Masters also remarks that “few have done more for the poet community than Bob Holman,” and then goes on to list just some of what Holman did for the poetry community, which is indeed substantial. Then there was the artist, George Schneeman, about whom he confesses, “Oh how I wanted to have my/ portrait painted by George Schneeman;/ it’d be like an admission to/ Valhalla, local acceptance/ to a cognoscenti that felt/ like the family I could see/ as rooting my diaphanous desperation.”

It was a time of late nights at the bar after readings, cheap rents, and poets taking charge of the publishing aspect by producing their own mags and publishing books. Crony books is Greg’s own imprint; having book and magazine experience, he gets his books out in the world like those writers did in the past such as Stein, Coleridge, Shelley, Dickens. It was the world of mimeos, and there was a feeling of unity with a common purpose to spread the word of poetry to whomever would listen. It was a time of conversation, and perhaps debate, of late nights spent talking until the early morning. People made themselves available, friendships were forged, a sense of a community thrived and produced works in opposition to the mainstream poetry world.

But that world has all but vanished. Greg Masters writes:

Yes, gone the community of

artists attuned to the lyre,

enflamed in the molten focus,

deliberate and awry in

pursuit of the available

and distant peculiarities.

•

The landscape also changed when rich investors moved in to buy up the Lower East Side and rents skyrocketed and older tenants were forced out:

Bit by bit, mom-and-pop shops – that

for decades had serviced locals –

began vanishing, avarice

steered new landlords playing the game

of speculation, taking a

risk on imperfect properties.

And affordable housing is as much of a problem today as it was, say, in the ’80s. Just one example: “In 1989,” Lance Freeman writes, “17% of renters paid more than 50% of their income for rent; in 1999, 20% did. Thus, during the period of the longest economic boom in history scarcely any progress was made in the arena of affordable housing.”

My own experiences living in a semi-rent controlled apartment in the early ’90s and working in a bookstore confirm this analysis. I was earning a little over $400 a week and my rent was $800. I lived next to a coke dealer in an adjacent apartment, a heavy drinker upstairs who fought with his girlfriend on a daily basis, and the sound of a booming bass caused the kitchen floor to vibrate every night for almost a year. I often thought the landlord’s refusal to plaster a large crack on the closet ceiling or to deal with the bedbug problem that arose suddenly were attempts to cause me to vacate my apartment so he could raise the rent 50%.

There was once a fire in the apartment above mine that caused the ceiling to partially collapse onto my floor, barely missing my bed. This occurred during the winter. The building was evacuated and all the tenants were hauled into a bus which was extremely cold. When the repair was done on my damaged apartment, I was told I could not move back into my former apartment, as previously promised, but had to move into a much smaller apartment one floor up because the rent for the now renovated apartment had doubled.

After this, my rent increased by $25 a year. My yearly raise from my job was 25 cents, I kid you not. I lived like that for close to a decade, knowing that soon my paycheck would not be able to pay the rent. A love of jazz and poetry held me up against the desperate reality. Affordable housing and other issues regarding urban life bridge the gap between poetry and politics. A person’s life is political. And I know many poets who have experienced similar problems.

•

Masters speaks of how The Poetry Project in those days, was

a safe base free from the “academic

stink” most of us decided was

irrelevant to our demand

to connect – without delay – to

the “starry dynamo,” as we’d

come across it in “Howl,” or more

particularly, what the streets

of Manhattan were presenting

Not every poet has an M.F.A. and a position in the academy, however tenuous, and often poets in the past chose other options and travelled different paths, often diverging from the central scene, and thus are harder to locate in the current debates surrounding poetry and politics. I don’t have an M.F.A.. I lost my apartment when my unemployment ran out and I relied on friends to help me get back on my feet. But I never lost the faith. Masters writes:

We were young, nothing was the least

inevitable, we coasted

drunk on the momentum of our

shared artistic purpose in the

unfolding specter of days and

nights, beholden as any faith.

•

In the title poem, “It wasn’t supposed to be like this,” Masters writes about the baby boomer generation that “There’s so much we didn’t do and/ so much we didn’t accomplish./ We fade leaving you youngins with/ an ailing planet fuming with/ detritus from bad decisions.” Who could have seen the rise of White Supremacy in this country, or the attacks on the LGBTQ? community or the murder of so many African-Americans, or the demonization and abuse of immigrant children at the border, and a Republican Party so obsessed with greed and power they are still unwilling to except the election results that made Joe Biden our 46th president.

Perhaps we are all complicit. As Masters writes, “The brothers and sisters nurtured/ in the Age of Aquarius/ assimilated into the/ realm of family normalcy/ or sedated their weary selves/ with drugs, work fetish or sit-coms.” This country is at fault for valuing money and profit over human lives, for the price of everything going up, but not the federal minimum wage. Masters writes about Alice and Ted, that they led

a subtle

revolt against the dream landscape

America was pretending

to offer its more gullible. Dedication to your passion,

the rest superfluous, they said,

without having to pronounce it.

•

David-Baptiste Chirot, in his essay “Raw War” about Amiri Baraka’s essay, “Why American Poetry is Boring, Again” writes, that for Baraka, in these times, “a poetry of the ‘the outdoors,’ of the actual, is being eschewed. Instead there is a desire for belonging, safety, all the comforts of Homeland Security.” In 2012, I filmed, alone and with a small point-and-shoot Canon camera, homeless vets, former drug addicts, and gang members in New Jersey and on the Lower East Side. I was able to document the language and face of despair and anger otherwise silenced in the media. Certain voices were also silenced due to certain trends of the past 30 years in poetry. That’s no surprise, of course, as changing fashions rule in poetics as in clothing.

•

Masters’ wonderful book, It Wasn’t Supposed to Be Like This, is a testament to freedom. It is a book of hope for future generations; it should be read by poets under 30 so they can get the real story, the facts, about those poets who paved the way for them in the early years. Their message resounds with urgent clarity in Masters’ book.

A good source is Public Access Poetry, a program that aired during the late ’70s and featured many of the poets in Master’s book giving poetry readings. PennSound has uploaded the crucial series on its website. But I believe everyone should read this book. Now. I sincerely thank Greg Masters for writing it.

Postscript: To the memory of Lewis Warsh (1944-2020)

There is a poem by Lewis Warsh called “Scenes from the Road,” in Harris Schiff’s xeroxed, hand-stapled magazine from the early ’70s, “The Harris Review,” that addresses the various roads taken or not taken by poets “on the scene.” I would like to close with this beautiful sentiment. It was on my mind while I was reading Masters’ book:

Some fade off the scene for indefinite periods of time, others stay on it forever … Some live in apartments, others buy or rent houses & farms in the country … Some take good care of themselves while others lie in bed worrying about their health … Some edit magazines. Some drift off & get into other things … Others just leave it all behind, while still others remain blinded by it all. Almost everyone comes through.

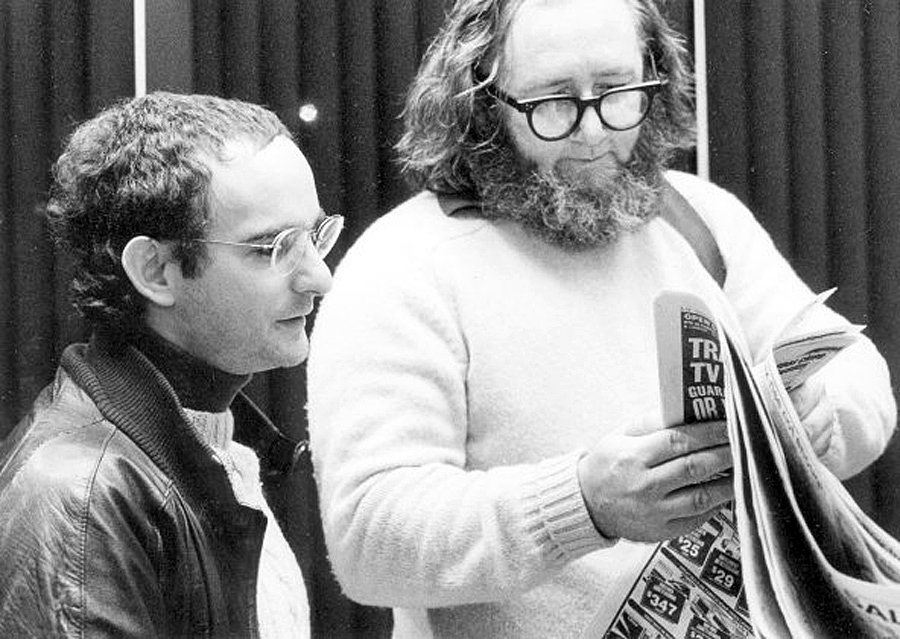

GREG MASTERS has lived in Manhattan’s East Village for 45 years. He co-edited the literary magazine Mag City, edited The Poetry Project Newsletter, was an art critic for a number of years, and is the author of nine books from his imprint Crony Books (http://www.cronybooks.net). Kate Previte photo.

PETER VALENTE is a writer, translator, and filmmaker. He is the author of 11 books, including a translation of Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions), which received a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly. Recently published was the collection Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum Books). Forthcoming is his translation of Gérard de Nerval’s The Illuminated (Wakefield Press), out later this year, and his translation of Nicolas Pages by Guillaume Dustan, out next year from Semiotext(e). He’s presently working on editing a book on Harry Smith. Twenty-four of his short films have been screened at Anthology Film Archives.

PETER VALENTE is a writer, translator, and filmmaker. He is the author of 11 books, including a translation of Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions), which received a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly. Recently published was the collection Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum Books). Forthcoming is his translation of Gérard de Nerval’s The Illuminated (Wakefield Press), out later this year, and his translation of Nicolas Pages by Guillaume Dustan, out next year from Semiotext(e). He’s presently working on editing a book on Harry Smith. Twenty-four of his short films have been screened at Anthology Film Archives.