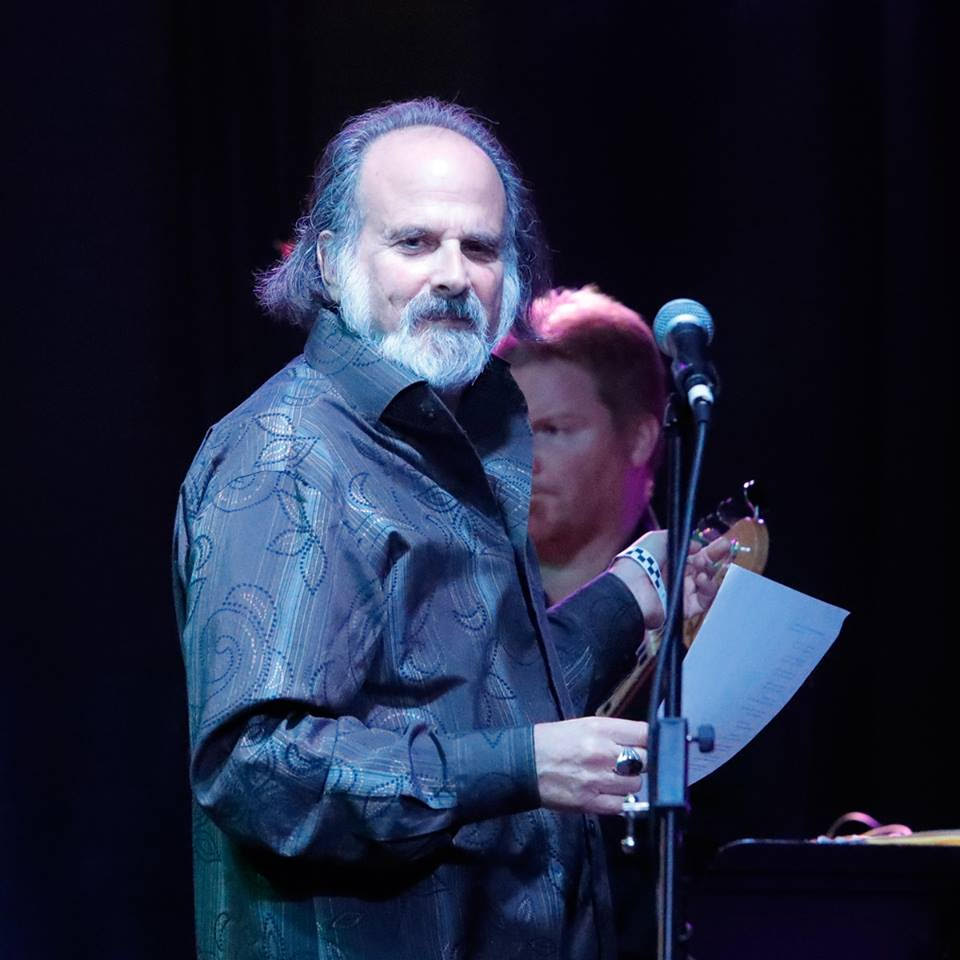

Bob Howard photo

Bob Howard photo

Interview by Wanda Phipps

I’ve known Michael Rothenberg for over two decades, worked with him on his legendary webzine Big Bridge, and followed his many artistic projects over the years. I checked in with him recently to have a more in-depth conversation about art, life, and what he has planned as the world begins to re-open.

Boog City: I’ve known you for years, as a wonderful writer, editor of the online arts journal Big Bridge, as well as an organizer of 100 Thousand Poets for Change. But how did you become a visual artist?

Michael Rothenberg: About 10 years ago I became close friends with the wonderful California painter Jim Spitzer. I used to go over to his house to visit him a couple of times a week. I needed a place to go and fight with someone other than whatever it was that was going on at home.

Jim would set up an easel for me, some Masonite boards, and give me full run of his brushes and paints. I would make a mess, and we would talk, and argue about politics.

Jim was hard of hearing so the news on the television set would be blasting loud while we painted. It was not an especially contemplative environment. But the love was there, and we painted through the chaos.

I don’t know if that was painting that I was doing. I mean, I painted, but I don’t think there was much art in it. I was a kid with crayons, but it was a good excuse to get out of the house, and I liked to see the colors splashing on the canvas. That is what I did, I smeared and splashed. I could not make anything look like anything, so I guess you could say I was “interested” in abstract art.

Terri Carrion, artist Jim Spitzer, and Michael Rothenberg in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Terri Carrion, artist Jim Spitzer, and Michael Rothenberg in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Jim reminded me that abstract art wasn’t just throwing paint on a canvas. “Yes, Jim, I know, I know.” Jim didn’t offer much instruction. Mainly, he would come over to me while I was intensely making a mess and take the paintbrush out of my hand and paint over something I had painted. This made me furious. After all, it was my mess not his.

When I got angry, he would smile in a twisted way. Then he would say, “If you liked the way it was before, then paint it back to the way it was.” This was like asking me to walk on water.

So that was an introduction to being an artist, but I dropped it. I think I was there for the social interaction more than anything. I had writing to do. I never painted anything I thought was complete, nothing I would ever call a real painting. It was a mess without resolve. I never took it seriously.

Eventually, I stopped painting, and Jim and I would talk on the phone and go to lunch. I would go to his studio, look at what he was working on and we would kvetch to each other.

Four years ago, Terri and I moved from California to Tallahassee. Once in Tally, I kept my focus on my poetry and poetry performance with local musicians.

Then a couple of years ago my son passed away. I went to a grief counselor. After several months, the grief counselor recommended I go to an art therapist. I was reluctant. I thought my grief counselor was just trying to shut me up, but she explained there are some things you can say, some emotions you can get to through art that you might not get to through words. That made sense to me, so I agreed to see an art therapist.

At our first meeting, the art therapist put drawing paper, colored pens, and crayons on the table between us. She let me know that we could draw and talk, or not draw and just talk. It was up to me. I think she suggested I draw some things based on prompts just to get me to touch the materials, but it was optional.

Bottom line, while we were talking, I started to draw, and then I went home and continued to draw. I went to the art store and bought markers, acrylics, watercolor paints and paper, and pens. And now I have an easel, spatulas, and spray paints. The art supply addiction kicked in. I have not stopped my engagement with visual art since then.

Now, I sometimes feel I have completed a painting or drawing. I seem to know more of what I am trying to achieve in certain pieces but always welcome the surprise. If I am not surprised, I will do something to upend myself to find out what is on the other side of what I am doing.

I share the images on Facebook and Instagram, and I am always baffled when people tell me they like them and call me an artist. Some people say I should sell them, but there is a certain freedom to knowing that whatever it is I am doing I don’t have to make a career out of it. God forbid another reckless career. So, I have hundreds of images in sleeves. I put them away and don’t think much about them.

I am grateful to my grief counselor for sending me in this direction. Making art has helped me through some very hard times.

Do you feel that your visual art inspires or feeds your writing or vice versa? And if so, how?

There seems to be a fine line between poetry and visual art, at least in my brain. I mean, I know the difference between the two, but their similarity is undeniable. It is a personal perspective of course: line, color plane, space, abstraction, therapy, sublime madness, bloody and bloodless vocabulary. A perspective of unity. A language. Like poetry.

It all tells a story, sometimes narrative, sometimes juxtapositional, always out of experience. I am losing myself in the discovery. Like in writing, as I approach writing, as I approach the visual world, I live in the discovery. Maybe I can amuse you with it. Maybe I will bore you. Boring you is not intentional but not infrequent.

So yes, the answer to your question, visual art feeds my writing and my writing feeds my art. It is all my mind moving back and forth between physical and non-physical manifestations, with a variance in tools and vocabulary. Does that make sense? Some images are words, and some words are visual …

Could you tell me a little bit about your background. When and how did you start writing?

I was born and raised in Miami Beach, Fla. in 1951. My father was an attorney and real estate developer. He was also a boxing enthusiast. My mother was a housewife and was interested in sculpting but mostly kept the family in order. I had one brother, Bruce.

When Bruce was in his twenties, he wanted to be a photographer. He went to San Francisco Art Institute, but soon after graduation abandoned the arts. After a brief engagement as my business partner in a tropical plant nursery in Pacifica, Calif., my brother departed to Nob Hill where he spent 35 years operating a men’s haberdashery selling pre-embargo Cuban cigars.

My mother’s art interests rubbed off on me. When I was a kid, I became interested in poetry. When I was about six years old Susie Starfish and Peter Porpoise was my favorite childhood book. I would try to rewrite the book in my own poetry.

When I was around 12 years old, my father’s business in real estate brought my family out to the Florida swamplands for fishing, specifically the city of Everglades, where nature became my companion and obsession.

In 1968, at 17 years old, I was turned on to the beat poets. My mother bought me a copy of On the Road. I don’t think she knew what she was doing. Somewhere I picked up a copy of Michael McClure’s Meat Science Essays. McClure cracked open my skull. Then a friend who had an older sister living in The Village passed on a few mind-blowing record albums, including Ginsberg reading “Howl” and Ferlinghetti reading from A Coney Island of the Mind. McClure, Ginsberg, and Ferlinghetti expanded my thinking beyond the secular province of Miami Beach and seduced me into poetry.

Mrs. Halperin, my 10th grade English teacher, taught the Romantics. That seemed like something to be, a Romantic poet. It was the ’60s. The stars were aligned. It was “the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.” Yes, I would be a poet. My poetry would be rooted in nature because that is where I found my inspiration and solace.

After some stops and starts I graduated from UNC-Chapel Hill with B.A. in English. Both my parents were supportive of my interest in poetry, but I think they would have been more comfortable if I had become a teacher, they wanted me to have a real profession, but they did not block me from my interests and life path decisions.

In the 1970s, my ex-wife, Nancy Davis, my brother, and I opened-up a tropical plant nursery, Shelldance, in Pacifica, specializing in bromeliads and orchids. I met Nancy at a plant store in Montgomery, Ala. I had no experience in horticulture, but I was sure my love of plants, Nancy’s experience in a plant store, and my brother’s business acumen, would be adequate to help us sustain ourselves growing and selling tropical plants for a living.

Cosmos Rothenberg, Michael Rothenberg, Philip Whalen and Joanne Kyger. Nancy Davis photo.

Cosmos Rothenberg, Michael Rothenberg, Philip Whalen and Joanne Kyger. Nancy Davis photo.

It was the nursery that brought in Joanne Kyger, Michael McClure, and Philip Whalen, that is how those connections were made, our friendship began around the nursery, and common interests in nature, and of course poetry was the embracing flow. These poets became my new family, mentors, and confidants for a lifetime. And the activism of the writers who most influenced me as a teenager ignited in me the battle cry to save the planet.

While in Pacifica, I helped lead local environmental actions that stopped major coastal developments that would destroy wildlife habitat. That was the nature of the Everglades speaking up.

My brother departed Shelldance for Nob Hill. I departed the nursery in the 1990s and worked as a songwriter for a few years, started up Bigbridge.org, and eventually remarried.

I met Terri Carrion in Florida, where I went to take care of my mother until her death after a bout of caretaking for Philip Whalen until he died. Eventually Terri and I moved back to California to the redwoods in Sonoma County where we began 100 Thousand Poets for Change and got deeply involved in police accountability issues.

What or who do you consider your major influences and inspiration as a writer?

The Romantics. Keats mostly. Nature. Art. Activism. Ginsberg, McClure, Kyger. Whalen, Celan, Whitman, Hart Crane, Black Mountain poets, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, René Char, William Burroughs, Sylvia Plath, James Joyce, Laurence Sterne, Lautremont, and Emily Dickinson.

Forrest Reed who taught me modern poetry at UNC including Pound, Dylan Thomas, and Eliot, and also taught me Shakespeare. Ed Dorn’s Gunslinger. Amiri Baraka and David Meltzer who inspired me toward performance, also Jayne Cortez. Denise Levertov. Lorca. One Hundred Poems from The Chinese, edited by Kenneth Rexroth. Mayakovsky and Anna Akhmatova.

Michael Rothenberg and David Meltzer on The Rockpile Tour. Terri Carrion photo.

Michael Rothenberg and David Meltzer on The Rockpile Tour. Terri Carrion photo.

Is there a pattern here? Terri Gilliam’s Brazil. El Topo. Jean Cocteau. Henry Miller, Henry Miller, and Henry Miller. Langston Hughes, Mallarme, Apollinaire, Valery, and Blaise Cendrars. Japanese Poetic Diaries by Earl Miner …

I know you have written fiction as well as poetry, could you speak a bit about how the decision is made for an idea to take form as a poem as opposed to a piece of fiction?

I don’t think I can answer that question directly. I write what and how something comes to me. Sometimes I have felt I want to take a big breath and so get ready for something long, but it is almost physical and not specifically an idea. Though there are some concept ideas that form with a novel that are a bit more premeditated than with a poem.

Poems are like breathing for me. I do it. Novels seem to be more driven by some sort of pervasive ambition.

Nevertheless, I am always curious about different writing forms. I have always been interested in writing overall and wondered what writing a novel would be like.

It is not easy. It is like marathon running as opposed to a 50-yard dash. In 2000, I made my first attempt at a novel with the eco-spy novel, Punk Rockwell (Tropical Press). Then I had a vision that led me to write the poetic novel The Drums of Grace.

The Drums of Grace is a dystopian story about music and censorship. It feels like animation. Something between Alice in Wonderland and Mad Max. A fantasy fable and science fiction. It suggests multi-media, a play, a movie. I like that. And that it is something of fiction and of poetry as a genre is compelling. It is political and rooted in pop culture.

Some time after finishing Drums I became engrossed in the long novel project, “Goatland.” It is abstract and poetic, dystopian, blatantly political, and “experimental.” “Goatland” filled up my head and seized my imagination. What will the future bring? It was fun to write.

What are you working on now?

Over the past year, 2020, I made it my goal to go over every poem I have ever written that remains unpublished, edit the poems, and place them into manuscripts.

The Pillars (Contagion Press) and I Murdered Elvis (Alien Buddha Press) came out of that revision work. In Memory of A Banyan Tree, Poems of the Outside World 1985-2020, a collection of nature poems will be published by Lost Horse Press in 2022.

I recently redrafted “Goatland” and I have not begun to look for a publisher yet. A selection of that novel is represented here in Boog City.

“The Drums of Grace” is being recorded in an audiobook by Randy Thomas, America’s premiere female live voice announcer. I am still seeking a print publisher for “Drums of Grace.”

There is a children’s book, “Look At That Mountain,” that needs a publisher. This is starting to sound like an advertisement.

I have also completed “Walking On Air,” a book of poems written for my son who died from a drug overdose. I consider “Walking On Air” my most important book, and I am looking for a publisher who will do that book justice.

So, in answer to your question. I am mainly working on placing my manuscripts with publishers. That is plenty to work on. And of course, there is 100 Thousand Poets for Change which continues to thrive despite covid restraints.

Click to Visit

Fiction from Michael Rothenberg

Poetry from Michael Rothenberg

Michael Rothenberg Comes Alive!

Drawing The Shade (Dos Madres Press)

The Pillars (Quaranzine Press)

WANDA PHIPPS is a writer/translator/ editor living in NYC (http://mindhoney.com). Her books include Field of Wanting: Poems of Desire and Wake-Up Calls: 66 Morning Poems. Her poetry has been translated into Ukrainian, Hungarian, Arabic, Galician, and Bangla. She’s received awards from The New York Foundation for the Arts, The National Theater Translation Fund, and others. As a founding member of Yara Arts Group she has collaborated on numerous theatrical productions presented in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Siberia, and at La MaMa, E.T.C. in NYC. She’s curated reading series at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church and written about the arts for Time Out New York, Paper Magazine, and About.com. Her new book, Mind Honey, is forthcoming from Autonomedia.

WANDA PHIPPS is a writer/translator/ editor living in NYC (http://mindhoney.com). Her books include Field of Wanting: Poems of Desire and Wake-Up Calls: 66 Morning Poems. Her poetry has been translated into Ukrainian, Hungarian, Arabic, Galician, and Bangla. She’s received awards from The New York Foundation for the Arts, The National Theater Translation Fund, and others. As a founding member of Yara Arts Group she has collaborated on numerous theatrical productions presented in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Siberia, and at La MaMa, E.T.C. in NYC. She’s curated reading series at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church and written about the arts for Time Out New York, Paper Magazine, and About.com. Her new book, Mind Honey, is forthcoming from Autonomedia.

MICHAEL ROTHENBERG is co-founder of 100 Thousand Poets for Change, co-founder of Poets In Need, a non-profit 501(c) 3, assisting poets in crisis, and editor and publisher of BigBridge.org. His most recent books of poetry include Drawing The Shade (Dos Madres Press), The Pillars (Quaranzine Press) and I Murdered Elvis (Alien Buddha Press). In Memory of A Banyan Tree, Poems of the Outside World, 1985-2020, will be published by Lost Horse Press next year. Rothenberg currently lives in Tallahassee, Fla., where he is Florida State University Libraries Poet in Residence.

Michael Rothenberg’s Wikipedia

Art at Otoliths

Drawing The Shade (Dos Madres Press)

The Pillars (Quaranzine Press)