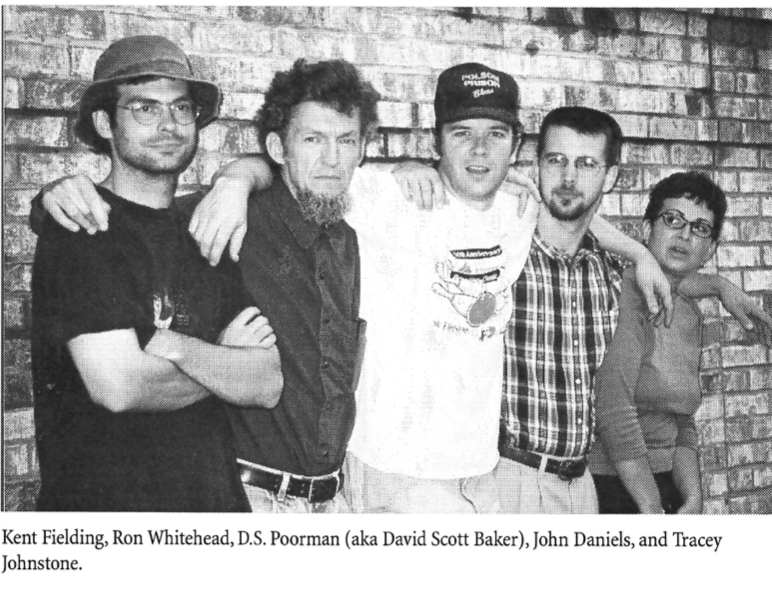

by Kent Fielding

D.S. Poorman became a cult figure around Louisville during the ’90s and early 2000s. The band Wodka wrote the theme song for his first novel, Macky Dunn Got Nothing to Lose, and D.S. read with them playing behind him like a rock star, dancing to the music when his poem or prose passage ended. Or he’d appear nude in something like the “Culture Mud Man,” an art performance where Louis Bickett, the creator, would plaster mud over the model promoting the healing nature of Earth. D.S. would walk naked onto the stage smiling and making eye contact with young women in the audience.

One of the first reviews for Macky Dunn compared D.S. Poorman to Hunter S. Thompson, and while D.S. Poorman wrote fiction (Thompson wrote journalism) both writers held a vehement distrust of law enforcement, a belief that law enforcement should be about protection of citizenry and not a search to punish potential drug users who might be smoking a joint in their upstairs bedroom. D.S. hated the comparison to Hunter, but he loved the coverage.

At the time D.S. lived in a compound on top of Jefferson Forest with a 10-foot fence around his house. He built this fence one weekend after someone wandered onto his yard. “Fuck,” he said. “They came up to my house and wanted to talk to me about my poetry and about the music I was playing. They heard Freakwater from the bottom of the hill and wanted to discuss the importance of bluegrass. I just want to keep the fuckheads out.”

He blasted his music into the forest at all hours, day or night. He also grew marijuana in the forest and was known to drink whiskey at any hour, often waking to gulp shots. He worshipped the night and wanted as little as possible to do with the mundane 9-5 world. He stayed awake all night and wrote, sleeping only when the sun came up.

He did outrageous things during the night like poster the city with broadsides discussing his political and literary views. He descended from his hill, a Grendel-type being, and postered the city at 2 am – “The world little knows what happens at 2 am,” he once stated. He’d spatter the walls of Louisville with the blood of words and took out enemies and those who sung against his view of heaven.  In 2000, he got into a spat with the literary editor of the Leo over some statements about poetics, and he posted broadsides all over town dismissing the editor and the editor’s baffling views of art (he compared the editor to a quack shaman selling “magical elixirs” that removed the enamel from the teeth of poetry). When the editor wrote back against D.S. in his Leo column, D.S. sent a note to the “Letters to the Editor” section, stating, “So and so has stumbled onto my playground and I intend to beat him up and take his lunch money.” D.S. pummeled the man and took his lunch.

In 2000, he got into a spat with the literary editor of the Leo over some statements about poetics, and he posted broadsides all over town dismissing the editor and the editor’s baffling views of art (he compared the editor to a quack shaman selling “magical elixirs” that removed the enamel from the teeth of poetry). When the editor wrote back against D.S. in his Leo column, D.S. sent a note to the “Letters to the Editor” section, stating, “So and so has stumbled onto my playground and I intend to beat him up and take his lunch money.” D.S. pummeled the man and took his lunch.

His playground was the metaphorical playground of literature; D.S. towered and created shadows over other local writers in those days and he raged on his typewriter. As a Grendel-type monster he ripped the editor to pieces and crunched his bones. All his broadsides were traps and this person had taken D.S.’s fire breathing worm that dangled on the hook. The argument with the editor had something to do with poetry and art, but really D.S. had seen this editor a year or so before at a 10-Foot Pole concert, in the sound booth, acting as if he were holding a rifle, taking aim, and shooting those dancing in front of the stage. This was right around the time of Columbine. D.S. became offended at the moral ineptitude as if those dancing didn’t matter and he carried a grudge. When he saw an article that reminded him of this lack of concern for people, he attacked. D.S. didn’t forgive, and it took a swimming pool of whiskey to make him forget.

D.S.’s broadsides could be reminiscent of Hunter S. Thompson’s Aspen Wall Posters, except, D.S. didn’t work with photos or art. It was all writing. He’d denounce Louisville’s hypocritical intellectuals or Louisville police, or he just promoted writers and work he admired. I remember one weekend driving around Louisville in D.S.’s windowless jeep and shouting haikus through a megaphone at people on street corners. We called it drive-by haiku (probably a terrible name but we never viewed poetry as violence). We’d spent the previous day writing haiku, writing all day, reading the work out loud to each other and commenting on it, until we got too drunk to write. I still remember a haiku he wrote: “9-to-5 with tie/ just wouldn’t do, without clothes/ he enjoys his work.” It’s a very adolescent poem, but it shows D.S.’s disgust with a 9-5 job; he’d rather work in the porn industry.

D.S. was invited to read at various events outside of Louisville including the New York Poetry Festival in 2000. I believe this was at the Nuyorican Poets Café, and until his health turned, he had moments where he was the larger-than-life outlaw, but he hated terms like “outlaw poet” or “outsider,” he would name himself, and he did.

KENT FIELDING is a poet, teacher, activist. He co-founded the literary renaissance and White Fields Press in 1992. His work has appeared in various journals and he is the author of Chief Iffucan.