by Ryan Masters

I first met the poet and writer D.S. Poorman through the eyes of Kent Fielding during the dark years Fielding and I spent embedded in the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ M.F.A. program together. A winter in Fairbanks was like an eight-month cocktail that never really cured your hangover—three parts alcohol, one part melatonin, a sprinkling of suicidal thoughts, hold the sunlight. Between the winters, too-short summers burst into life like a billion biting insects winging into the sky at once. It was a radical, schizophrenic place.

Amid the chaos, Fielding shone like an oil lamp, casting shadow stories on the cabin wall. Bristling with a rock-music passion for literature, he regaled me with first-person tales of Beat, hippie, and punk heroes, literary festivals where no one slept for three days, and Saga-length poems set in Kentucky.

In 1998, I was a young aspiring novelist who’d just published his first poem in The Iowa Review—a feat I was desperately, unsuccessfully, attempting to replicate. Fielding showed me pages of the D.S. Poorman manuscript that would become Mackie Dunn Has Nothing to Lose. The prose, while largely unedited, possessed a jittery energy that felt like coming off blotter acid back when we all still thought they put strychnine in it. In other words, Mackie Dunn crackled in a way my own novel did not.

After grad school, I went to Jamaica and kicked off the new millennium behind bars before fleeing north to Quebec. In Montreal, I taught ESL, formally separated from my first wife, dabbled with sobriety, and tried to recover from the trauma of Alaska. When Fielding and Poorman rolled into town late in the summer of 2000, I was no Mr. Bojangles.

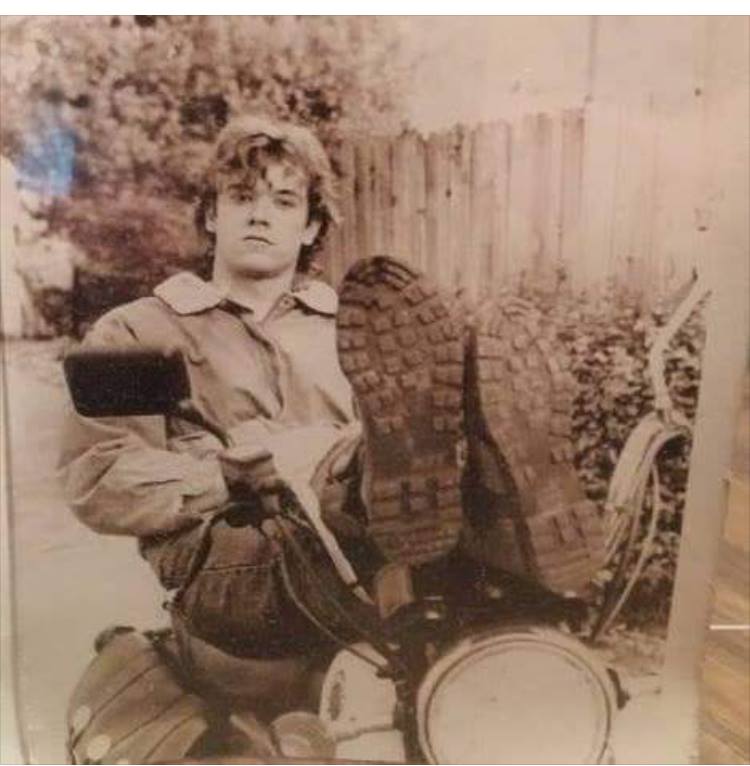

Dave Baker was quieter than I expected—polite in the way Southern boys can be, I guess, but confident. He’d just self-published Mackie Dunn. The novel’s cover design couldn’t be lazier, and I found multiple typos within minutes, yet I couldn’t help envying the achievement. I’d finished my own novel, but decided it was so bad it needed to be burned in a metal pail.

Despite my mood, Poorman’s optimism was infectious. He shared Fielding’s belief in the transformational power of literature. They had plans—insane plans that were part literary promotion, part Gonzo goof. Poorman was willing to bet everything he had on his own talent. Just like Mackie Dunn, the motherfucker apparently had nothing to lose.

Mackie Dunn was never going to be featured in The New York Times. Yet, as we walked parks of Montreal drinking strong Quebecois beer, I remember thinking that Poorman might still have a great book in him. Like the rest of us, he just needed to get out of his own way.

The next year, I took up Fielding and Poorman’s offer to read and play music at the 2001 Isomniacathon in Louisville, Ky.. In addition to drinking enough whiskey to kill a classroom of children, I experienced the Kentucky Literary Renaissance firsthand and caught a wicked set of live music by an unknown band named My Morning Jacket. At some point during the blur of those 72 hours, I heard Poorman read his poetry for the first time. It was a revelation. In my opinion, his verse was leagues ahead of his prose.

That long, devastating weekend changed my opinion of the man—especially once I realized that Poorman was something of a punk legend in Louisville. He had a reputation for bad behavior and weird stunts that surprised me until I experienced him totally hammered. Nothing irritated Poorman quite so much as the over-the-top self-promotion of hippie poets such as Louisville’s Ron Whitehead. Like a lot of Gen X artists, Poorman wanted the public recognition, but hated himself for wanting it. Despite working tirelessly behind the scenes to make the 2001 Insomniacathon a reality, Poorman never got much credit for it. (In fact, until recently, I was certain Whitehead had put on the event with Fielding, not Poorman.)

Alas, when the Insomniacathon ended and I said goodbye to D.S., it would be for the final time. Over the next 20 years or so, Fielding would fill me in on his friend’s increasingly bizarre pursuits. At one point, D.S. began building elaborate books out of wood, one of which, The Largest Poetry Book in the World, was the size of a door. Eventually the updates from Fielding had less to do with literature or carpentry and more to do with Poorman’s health and legal issues. I began to wonder where all that poetry had gone.

Fielding called me with the news that Poorman was dead in 2020. I thought back to the man’s poetry from the Insomniacathon nearly 20 years earlier, wishing I could hear his voice again. I wondered if his lonely, illuminated words still touched me in the same way.

A true friend, Fielding rescued his dead buddy’s collected works of poetry off a discarded hard drive before they could disappear forever. When he told me he was editing a volume of Poorman’s verse that would be published by Radial Books, I volunteered to take a look. Editing a dead friend’s work is a dicey proposition. How could he approach the work objectively?

Fortunately, Poorman’s poetry was stronger and even more heartbreaking than I’d remembered, and Fielding’s deft edit didn’t de-claw Poorman’s demons. A lesser editor might try to hide his friend’s fragility and protect Dave Baker, the man behind the persona, but the poems in Before the Grave are as raw, brilliant, and genuine as the man who wrote them. Nice work, Poorman. You can rest easy now, man.

Ryan Masters (RyanMasters831.com) is a writer, poet, musician, and bodysurfer from Santa Cruz, Calif.

Ryan Masters (RyanMasters831.com) is a writer, poet, musician, and bodysurfer from Santa Cruz, Calif.